Wine used to toast CGD gene therapy trial linked to decades-long scientific journey

When Brenden Whittaker of Columbus, Ohio, the first patient treated with gene therapy for chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), showed successful engraftment last winter, the gene therapy team lifted glasses for a celebratory toast. The wine they sipped was no ordinary wine. The 2012 Bordeaux blend came from an award-winning California vineyard owned and operated by Robert Baehner, MD, a pioneering pediatric hematologist with ties to Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center.

Decades before, Baehner had done fundamental research in CGD, an inherited immune system disorder that occurs when phagocytes, white blood cells that normally help the body fight infection, cannot kill the germs they ingest and thus cannot protect the body from bacterial and fungal infections.

Children with CGD are often healthy at birth, but develop severe infections in infancy and early childhood from bacteria that would cause mild disease or no illness at all in a healthy child. This was true for Whittaker. Diagnosed with CGD when he was 1, his disease became increasingly severe, forcing him to quit school several years ago.

“It seemed to get harder as I got older,” he says.

At 17, Whittaker suffered intractable pneumonia and had part of his right lung removed. He spent much of the past year in the hospital for a lung infection and had part of his liver removed for infection.

A missing enzyme and a cloned gene

Until the 1960s, the only way to diagnose CGD was the presence of granulomas — masses of inflammatory tissue in the lungs, skin, liver, lymph nodes, intestines or other locations that form in response to chronic infection. Baehner, then a pediatric hematology/oncology fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital under the direction of David G. Nathan, MD, developed the nitroblue tetrazolium test (NBT) for CGD. It quickly became the gold standard, probing infection-fighting phagocytes for production of an enzyme that acts like a bacteria-killing bleach. In children with CGD, this enzyme is missing.

“This was the earliest fundamental observation, made before we even understood the complexity of the disease and the facets of the enzyme,” recalls Baehner, who went on to study the biology of phagocytes.

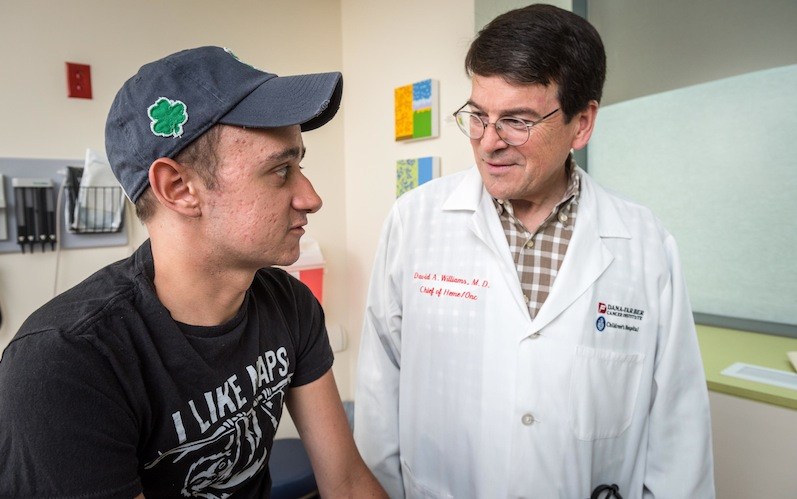

“NBT was a practice-changing test,” says Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s President David A. Williams, MD.

Williams worked in Baehner’s laboratory the summer after his first year at the Indiana University School of Medicine, when Baehner was chief of hematology at Indiana’s Riley Hospital for Children. He counts Baehner as one of his earliest and most influential mentors.

“Dr. Baehner in many ways is why I’m in science in pediatric hematology,” he says.

In the mid-1980s, Baehner took a sabbatical from Indiana to work in the Boston Children’s hematology laboratory of Stuart Orkin, MD. He brought with him genetic samples from an Indiana patient family with two X-linked diseases — CGD and Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

That sparked the Orkin laboratory’s interest in CGD research. In collaboration with the Boston Children’s lab of Louis Kunkel, PhD, who was interested in Duchenne, the lab used Baehner’s samples to clone the CGD gene.

Early gene-therapy challenges

Decades later, Williams founded Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s gene therapy program. Baehner had retired from his position as physician-in-chief at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles in 2007 and now runs Baehner Fournier Vineyards in Santa Ynez, Calif., with his wife.

Williams stayed in touch, and on his last visit, he told Baehner about an upcoming gene therapy trial for CGD — introducing into patients a healthy copy of the gene Baehner had helped clone in the 1980s. The hematologist-turned-winemaker presented his protégé with the bottle of award-winning wine and made a request: Use it to toast the first patient treated under the new protocol.

Early efforts at gene therapy for CGD had run into the same problems that plagued initial gene therapy trials for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (“bubble boy” disease) and Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. A significant number of patients in those early trials developed treatment-related leukemia.

Not giving up, physician-scientists worked to create safer viral vectors to deliver the corrected genes. Early results of the newer SCID-X and Wiskott-Aldrich trials have found no cases of leukemia and no apparent activation of cancer-causing oncogenes.

The new CGD gene therapy protocol employs a similarly modified vector. On December 18, 2015, 22-year-old Brenden Whittaker became the first CGD patient to be treated.

A toast

Soon after Whittaker’s treatment, Williams and his colleagues finally uncorked Baehner’s bottle of wine. The corrected gene — nearly 30 years after it was cloned — had successfully engrafted in Whittaker’s bone marrow.

“It took my breath away,” says Baehner now. “It’s almost like a father seeing his son be successful.”

On January 29, 2016, Whittaker returned to Ohio and remained in isolation until Easter to guard against infection. The corrected gene continued to take hold in his bone marrow, which began to produce functional phagocytes in his blood.

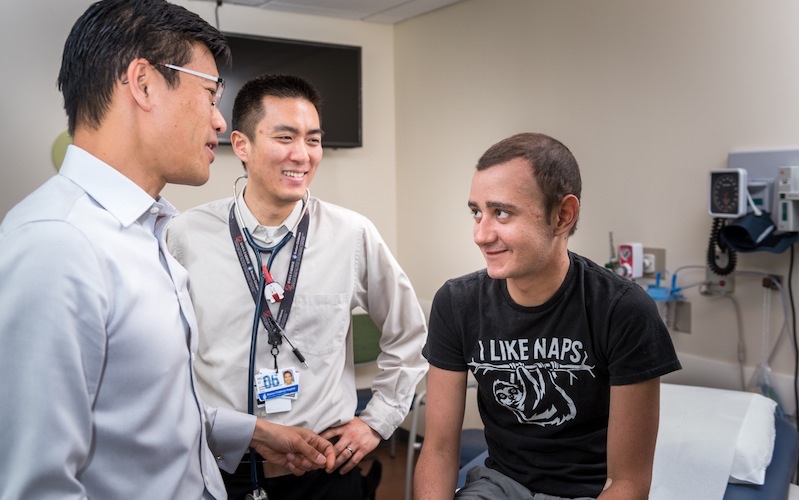

When Whittaker returned to Boston in early June for his six-month check-up, the clinicians who filled the exam room included two — Williams and Leo Wang, MD, PhD, co-investigator on the trial — who had toasted Whittaker’s engraftment with Baehner’s wine.

Whittaker is doing well, and his blood levels of corrected, infection-fighting neutrophils, a key type of phagocyte, are stable. In future tests, his clinicians will seek to confirm that the corrected CGD gene has not activated the oncogenes that likely caused leukemia in previous gene therapy trials.

Whittaker, meanwhile, is back working at a Columbus golf course, playing golf on the side — and thinking about a future. He hopes to return to college in January 2017.

His goal? “Medical school.”

Related Posts :

-

“A setback for a comeback”: Brody perseveres with Paget-Schroetter Syndrome

Baseball has been part of Brody Walsh’s story from the very start. Now 19 and a college sophomore, Brody pitches ...

-

Tough cookie: Steroid therapy helps Alessandra thrive with Diamond-Blackfan anemia

Two-year-old Alessandra is many things. She’s sweet, happy, curious, and, according to her parents, Ralph and Irma, a budding ...

-

Could a pill treat sickle cell disease?

The new gene therapies for sickle cell disease — including the gene-editing treatment Casgevy, based on research at Boston Children’s ...

-

A sickle cell first: Base editing, a new form of gene therapy, leaves Branden feeling ‘more than fine’

Though he doesn’t remember it, Branden Baptiste had his first sickle cell crisis at age 2. Through elementary school, he ...