Motor neurons made from patients’ cells reveal possible ALS drugs and targets

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a severe, fatal neurodegenerative disorder causing loss of motor neurons and voluntary muscle action. While mouse studies have identified potential treatments, these drugs have typically done very poorly in human trials.

“One of the most difficult challenges in drug discovery is identifying a target that has a key role in the disease process,” says Clifford Woolf, MD, PhD, director of the F.M. Kirby Neurobiology Center at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Working in collaboration with Pfizer, Woolf and colleagues have developed a high-throughput platform for discovering such targets. As described in Cell Reports, it uses motor neurons made from ALS patients themselves, coupled with imaging to measure the neurons’ hyperexcitability — the tendency to “fire” excessively — before and after exposure to different drugs.

By doing a screen aimed at reversing motor neuron hyperexcitability, we were able to discover new targets and disease mechanisms for ALS and confirm others in an unbiased way.”

Hyperexcitability is a cardinal feature of ALS. Using the platform, Woolf and first authors Xuan Huang, PhD, and Kasper Roet, PhD, in Woolf’s lab, confirm two known ALS drug targets. They also identify a new target that hadn’t been thought of in the context of ALS — and that’s amenable to treatment with existing drugs.

Detecting runaway action potentials

Woolf and colleagues previously showed that human motor neurons with ALS mutations are more excitable than normal motor neurons. That hyperexcitability — and the prospect of calming it — is at the heart of the discovery platform.

“Hyperexcitability makes the motor neurons more susceptible to degeneration and ultimately death,” Woolf says. “By doing a screen aimed at reversing this hyperexcitability, we were able to discover new targets and disease mechanisms for ALS and confirm others in an unbiased way.”

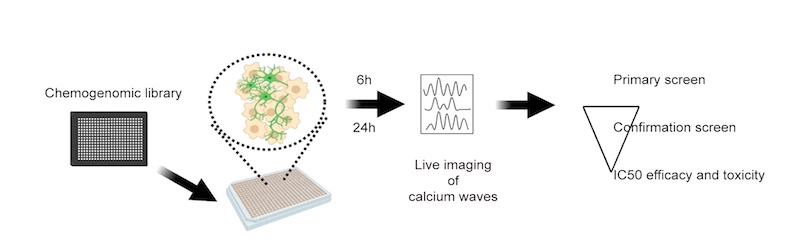

To create the motor neurons, the researchers obtained induced pluripotent stem cells made by the Harvard University lab of Kevin Eggan, PhD, using tissue samples of patients with ALS who carried the SOD1(A4V) mutation. They then differentiated the stem cells into motor neurons, loaded the neurons into 384-well plates, and exposed them to a variety of drugs.

To measure excitability, they used GCaMP imaging, which scans for a fluorescent marker of calcium levels. This is an indicator of how frequently the neurons are firing action potentials, and a measure of hyperexcitability.

Calming down hyperexcited neurons

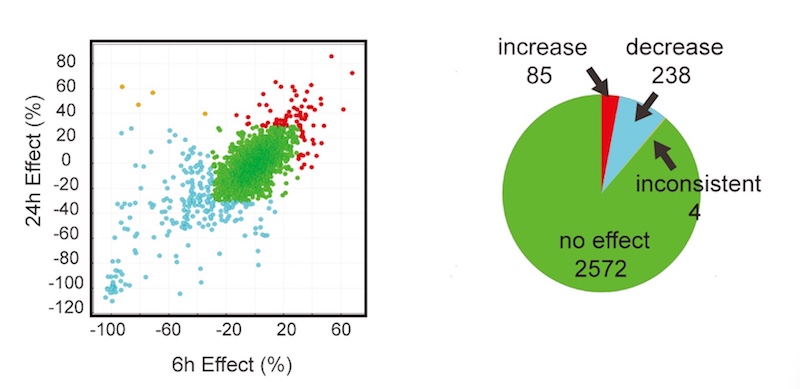

In all, the researchers screened a library of 2,900 drugs from Pfizer with known, annotated actions. After three screening rounds, they found 67 compounds that reduced hyperexcitability of the patient-derived motor neurons, without causing toxicity.

Further investigations homed in on 13 potential drug targets with the greatest effects. Seven of them belonged to two classes already known to be associated with ALS hyperexcitability: AMPA receptors and Kv7 potassium channels. (Kv7 channel-opening drugs were found to decrease motor neuron hyperexcitability in ALS in a recent clinical trial. QurAlis, a company co-founded by Woolf, Eggan, and Roet, is developing these drugs as therapies for ALS.)

The study also found a promising new class of candidate drugs, agonists to the dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2). These receptors’ role in motor neuron hyperexcitability had not previously been recognized. Moreover, some DRD2 agonists (bromocriptine, sumanirole) are commercially available, opening the possibility of testing them in patients with ALS.

“Our results show that neuronal excitability screens are a powerful platform for discovery of relevant, druggable targets,” says Woolf. “We believe it can be applied to other neurological diseases that involve neuronal excitability, such as epilepsy and other neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s disease.”

Future directions

In the meantime, Woolf is continuing to use human neuron screening platforms to identify novel targets for treating pain and neuropathy.

“Using patient-derived neurons to model disease and test large sets of compounds whose targets are known can be the driver for developing new therapies,” he says.

This study was funded by Target ALS, Pfizer Centers for Therapeutic Innovation (CTI), an ALSA Milton Safenowitz postdoctoral fellowship, and the National Institutes of Health. The authors declare the following competing financial interests: Roet, Woolf, and Eggan are founders of QurAlis Corporation. Roet is CEO of QurAlis. Coauthors Liying Zhang, Amy Brault, Allison Berg, Anne Jefferson, Jackie Klug-McLeod, Karen Leach, Fabien Vincent, Hongying Yang, Anthony Coyle, and Lyn Jones are current or previous employees of Pfizer Inc.

Visit the Woolf lab at Boston Children’s Hospital

Related Posts :

-

“Princess June” reigns supreme over Rasmussen syndrome

What do you call a “girly” 5-year-old who adores dolls and frilly nightgowns? If you’re one of June Pelletier’...

-

A new druggable cancer target: RNA-binding proteins on the cell surface

In 2021, research led by Ryan Flynn, MD, PhD, and his mentor, Nobel laureate Carolyn Bertozzi, PhD, opened a new chapter ...

-

The thalamus: A potential therapeutic target for neurodevelopmental disorders

Years ago, as a neurology resident, Chinfei Chen, MD, PhD, cared for a 20-year-old woman who had experienced a very ...

-

Could peripheral neuropathy be stopped before it starts?

An increase in high-fat, high-fructose foods in people’s diets has contributed to a dramatic increase in type 2 diabetes. This, ...