Clinical trials in children: Is there racial equity?

The treatments and interventions used in medicine are often based on the results of clinical trials. But trials involving adults haven’t always represented the population as a whole, tending to recruit mostly white middle-class people. As a result, it’s not clear how well the findings apply to people of other racial and ethnic backgrounds.

Do clinical trials in children have a similar limitation? Researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital investigated, and found much room for improvement despite some progress over the past decade.

“When we think about race and ethnicity, we’re not thinking of differences in biology, but about differences in lived experience,” says Dr. Eric Fleegler, a physician in the Division of Emergency Medicine who does research on health services. “Children of different ethnic and racial backgrounds may have different cultural perspectives, different access to resources, and different historical experiences. This may affect their health and their ability to participate in trials.”

In a study in JAMA Pediatrics, Dr. Fleegler and his colleagues reviewed 612 articles from top medical journals, from January 2011 through 2020, that reported clinical trial findings in children. Totaled up, these trials involved more than 500,000 children.

“Our first question was, how well are children of racial and ethnic backgrounds represented in clinical trials?” says Dr. Fleegler. “We also wanted to know how often researchers are even collecting this type of data.”

Diversity in pediatric clinical trials: A report card

Reporting of participants’ race and ethnicity in clinical trials improved over time, increasing by 8 percent per year for race and 11 percent per year for ethnicity. But even in 2020, only 83 percent of studies presented information on race and only 73 percent reported ethnicity.

Going in, the researchers predicted that Black and African American children would be underrepresented in clinical trials, because of a legacy of exploitation of Black people in unethical medical studies. Among the most infamous were the Tuskegee experiments, in which Black men with syphilis were left to suffer without treatment so scientists could study the effects of the disease.

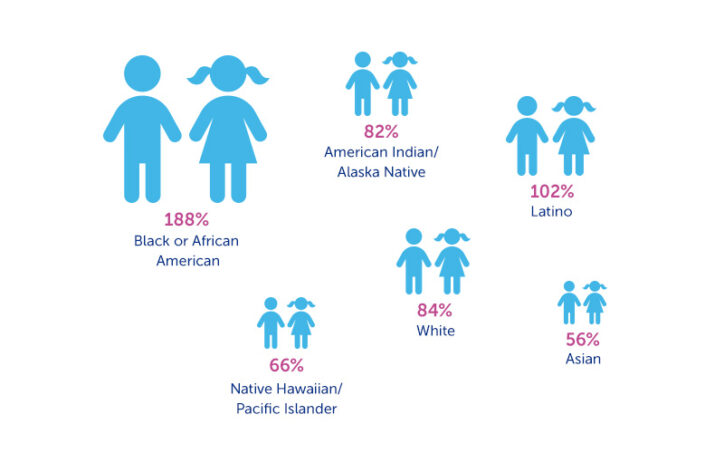

Because of this horrific history, the team was surprised to find that Black and African American children were overrepresented relative to their share of the population — almost double what would be expected.

“We were thinking this group would be hesitant about joining research studies,” Dr. Fleegler says. “But we saw really high representation.”

The researchers theorize that this may reflect that fact that most pediatric trials are centered in academic hospitals in urban areas, which tend to have larger Black or African American populations.

Asian children and others underrepresented

Enrollment of Latino children was on target relative to their share of the population, while white children were slightly underrepresented, at 84 percent of what would be expected.

Children classified as American Indian/Alaska Native were enrolled at 82 percent of the proportion expected, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders at 66 percent. However, when the researchers looked at the individual states in which the studies were done, the proportions moved closer to what would be expected for the state.

Most strikingly underrepresented, however, were children of Asian descent, who were enrolled at only 56 percent of the proportion expected.

“This may speak to diffusion of people who are Asian across the country, rather than being concentrated near large medical centers,” Dr. Fleegler speculates. “But it also suggests that a more conscious effort needs to be made to get a diverse population.”

A prescription for diversity

Dr. Fleegler suggests several ways researchers can improve diversity in pediatric trials. First, they need to make an explicit effort to enroll children from different ethnic groups, rather than leave that to chance. This may mean “going the extra mile” to approach parents of a race or ethnicity not the researchers’ own, and introducing different recruitment strategies.

Second, it’s important to try to understand why some parents are choosing not to enroll their children. Reasons could include everything from mistrust to difficulties traveling to the medical center for study visits. “Not a lot of people are asking this question,” Dr. Fleegler says.

Third, researchers should recruit people in different areas of the country, which have different population mixes and life experiences. A study based in Boston may not play out the same in children in Texas.

And finally, researchers need to consider factors beyond race and ethnicity that may affect clinical trial results. Medical studies are only now beginning to do this. Dr. Fleegler and his colleagues are currently investigating how well pediatric trials are recording children’s socioeconomic background, sexual orientation, gender identity, and language spoken at home.

“A large part of the population does not regularly speak English,” Fleegler says. “The vast majority of trials do not make efforts to enroll non-English speakers, and some studies purposely exclude them. Is that really what we want to do? We know that people who don’t speak English have a very different lived experience.”

Learn more about research in the Division of Emergency Medicine

Related Posts :

-

With a dose of health equity, brachial plexus study enrolls more patients

What drives a parent to say yes or no to enrolling their child in research? When a surprisingly high percent ...

-

Addressing inequities in asthma by focusing on children’s environments

Asthma strikes children in low-income urban areas especially hard, more often sending them to the hospital. For more than 20 years, ...

-

Census 2020: Every child counts to ensure health equity

With much of the world focused on the new coronavirus, it’s hard for many of us to think about ...

-

AI-enabled medical devices are burgeoning, but many haven’t been tested in children

Medical devices that incorporate artificial intelligence and machine learning are proliferating. In 2013, the FDA approved fewer than 10 such devices; by 2023, ...