Science Seen: An intestinal toxin’s trick, a potential cancer fighter

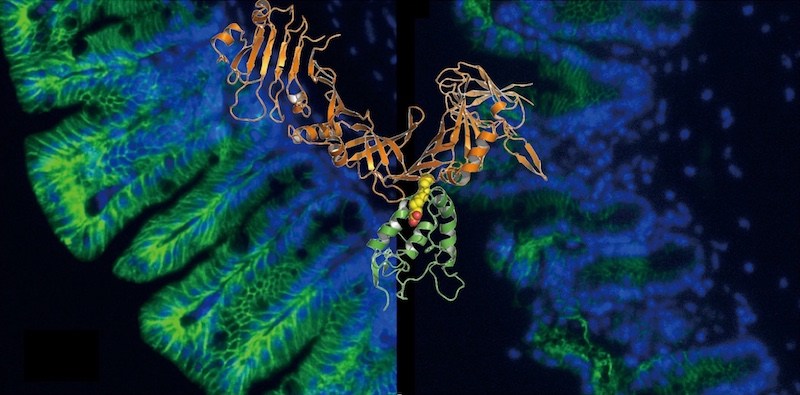

Clostridium difficile, also called “C. diff,” causes severe gastrointestinal tract infections and tops the CDC’s list of urgent drug-resistant threats. In work published in Nature in 2016, Min Dong, PhD, and colleagues found the elusive portal that enables a key C. diff toxin, toxin B, to enter the intestines’ outer cells and break down the intestinal barrier (above right).

Interestingly, the same portal, known as the Frizzled receptor, also receives signals that maintain the intestine’s stem cells. When toxin B docks, it blocks these signals, carried by a molecule known as Wnt. But exactly how it all works remained a puzzle — until new research published today in Science.

Liang Tao, PhD in Dong’s lab, working with the labs of Rongsheng Jin, PhD, at UC-Irvine, and Xi He, PhD, at Boston Children’s, captured the crystal structure of a fragment of toxin B (in orange above) as it joined to the Frizzled receptor (in green). The structure revealed lipid molecules within the Frizzled receptor (in yellow and red) that play a central role. Normally, when Wnt binds to Frizzled, it nudges these lipids aside. But the team showed that when the toxin fragment binds to Frizzled, it locks these lipids in place, preventing Wnt from engaging with the cell.

Just as stem cells rely on Wnt signaling for growth and regeneration, so do many cancers. Now that its mechanism is known, Dong thinks this toxin B fragment, which by itself isn’t toxic, could be a useful anti-cancer therapeutic. They’re currently developing a new generation of Wnt signaling modulators and testing them in animal models of cancer. (For further information, contact Boston Children’s Technology & Innovation Development Office at TIDO@childrens.harvard.edu.)

Related Posts :

-

A true hero’s journey: How a team approach helped Wolfie overcome pancreatitis

Wolfgang, affectionately known as “Wolfie,” is a bright and energetic 7-year-old with a quick wit and a love for making ...

-

A toast to BRD4: How acidity changes the immune response

It started with wine. Or more precisely, a conversation about it. "My colleagues and I were talking about how some ...

-

Team spirit: How working with an allergy psychologist got Amber back to cheering

A bubbly high schooler with lots of friends and a passion for competitive cheerleading: On the surface, Amber’s life ...

-

Thanks to Carter and his family, people are talking about spastic paraplegia

Nine-year-old Carter may be the most devoted — and popular — sports fan in his Connecticut town. “He loves all sports,” ...