Pain neurons activate immune cells, opening new treatment possibilities

For a long time, pain and inflammation were thought to be two separate biological responses. But new research by Boston Children’s Hospital and international collaborators suggests that the same sensory neurons that produce pain also trigger inflammation. And they do so by activating cells of the immune system, a relationship never described before.

This interaction between sensory neurons and the immune system, published in Nature Biotechnology, opens the door to new treatments for inflammation and inflammatory-based diseases.

Could inflammation have an immune component?

Key takeaways

The same sensory neurons that cause pain also trigger inflammation.

Neurons induce inflammation by stimulating immune cells.

This new discovery opens the door to potential new ways to treat inflammation.

Pain is a protective mechanism, alerting us to danger via a warning message carried to the spinal cord by specialized sensory neurons. If injury cannot be avoided, inflammation arises leading to redness, swelling, pain, and loss of function.

“All of those [signs] are actually related to the nervous system and not to the immune system,” says co-senior author Clifford Woolf, PhD, director of the F.M. Kirby Neurobiology Center at Boston Children’s.

But there has always been a lingering question whether inflammation has an immune component. “While it has been commonly known that immune cells flock to the site of tissue damage or pathogen invasion, it has not been understood whether the nervous system alone is sufficient to activate the immune system,” says Woolf, whose laboratory is devoted to the study of pain, inflammation, and neurodegenerative diseases.

Light stimulates sensory neurons

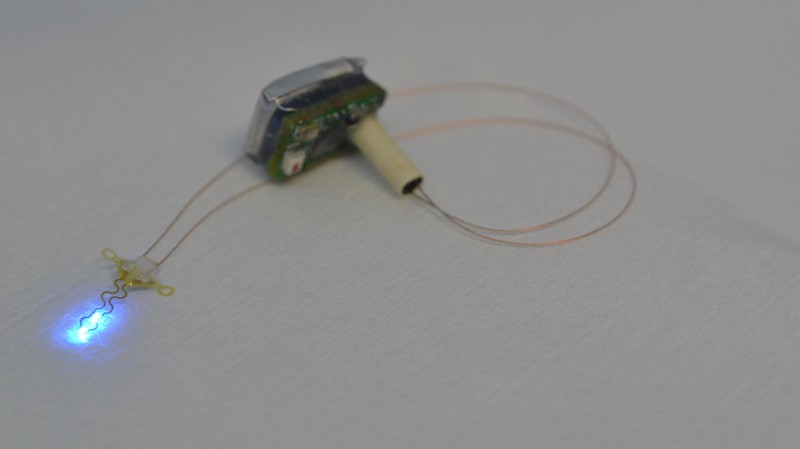

The study utilized optogenetics, a technique used to trigger, or modulate, selected neurons by shining light into neural tissues. When these nerves were triggered in live mice, researchers were able to measure the change in immune cell activation and the number of immune cells. According to Woolf, the challenge with using this technology for neurons has been to develop an approach that allows optical stimulation/illumination to occur repeatedly over many days without damaging the nerve and impacting the behavior of the animal.

To overcome these obstacles, researchers at the Center for Neuroprosthetics at the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) developed a solution. They engineered a soft implant that wraps around the sciatic nerve and delivers blue flashes of light on demand. The light selectively stimulates only the axons of pain-triggering neurons. Colleagues at the Swiss Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETHZ) developed a miniaturized chip for controlling the implant. Control tests confirmed that the optoelectronic implant did not interfere with the animal’s behavior in any way and did not induce side effects.

Activated neurons trigger immune cells

In their experiments, repeated optical stimulation of specific sensory neurons produced mild redness in the animal’s hindpaw, a clear sign of inflammation. Further study showed the presence of immune cells in skin samples, including T-cells and dendritic cells.

“Our study has provided an answer to the long-held question of whether those neurons that produce pain also produce immune-mediated inflammation,” says Woolf. “The answer is unequivocally ‘yes.’”

A new path for alleviating inflammation

Currently, inflammation is mostly treated with steroids — neuromodulators that suppress immune function. In general, neuromodulators act on a group of neurons.

This miniaturized implantable neurotechnology paves the way for future approaches to treat syndromes such as chronic pain or persistent inflammation with new neuromodulators.

This could be achieved either by blockading the release of neuromodulators or inhibiting their action on immune cells. An example would be targeting the neuropeptide CGRP, one of the most abundant neuromodulators. The FDA has already approved CGRP antibodies and CGRP receptor antagonists for migraine treatment.

“So, there are drugs out there that could potentially now be used to address some inflammatory conditions,” says Woolf. These include eczema, atopic dermatitis, and contact dermatitis — all skin conditions where there is a mix of pain, itching, and inflammation. Allergic airway inflammation, one form of asthma, might also benefit from such treatment.

Along with Woolf, Stéphanie Lacour (EPFL) and Qiuting Huang (ETHZ) are co-senior authors. Other contributors include: Frédéric Michoud, Ivan Furfaro, Outman Akouissi, and Katia Galan from EPFL, Geneva, Switzerland; Frédéric Michoud, Corey Seehus, Daniel Taub, Zihe Zhang, Aakanksha Jain, Rachel Moon, Benjamin Doyle, and Michael Tetreault from the F.M. Kirby Neurobiology Center, Boston Children’s Hospital; Philipp Schönle, Noé Brun, and Pascale Meier from ETHZ, Zurich, Switzerland; Sébastien Talbot Université de Montréal, Quebec, Canada; Liam E. Browne, Wolfson Institute for Biomedical Research, University College London, London, UK.

###

This research was supported by the Wellcome Trust and the Royal Society, the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme, the Bertarelli Foundation, the Swiss National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health.

Read more about research from the F.M. Kirby Neurobiology Center.

Related Posts :

-

A safe, pain-specific anesthetic shows preclinical promise

All current local anesthetics block sensory signals — pain — but they also interrupt motor signals, which can be problematic. For example, ...

-

Study highlights the severity of acute necrotizing encephalopathy in kids with the flu

For most children, influenza (flu) usually means unpleasant symptoms like a fever, sore throat, and achy muscles. But for a ...

-

“Princess June” reigns supreme over Rasmussen syndrome

What do you call a “girly” 5-year-old who adores dolls and frilly nightgowns? If you’re one of June Pelletier’...

-

Which pain medication is right for your child? What a pediatrician wants parents to know

There’s no shortage of safe and effective pain medications for children. Acetaminophen (commonly known as Tylenol), ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil), ...