Treating MAPCAs with unifocalization surgery and cardiology care

Children born with a rare form of tetralogy of Fallot (ToF) face a challenging type of congenital heart disease.

Known as ToF with pulmonary atresia and major aortopulmonary collateral arteries (MAPCAs), the condition often requires a child to have many operations and cardiology procedures to restore blood flow to the lungs and protect their heart from damage.

But a team of Boston Children’s heart specialists has found a way to effectively treat the condition while reducing the number of procedures a child has. Their pulmonary artery reconstruction team combines catheter-based therapies with unifocalization, a surgical procedure so specialized that Boston Children’s is one of only a few pediatric hospitals to offer it.

“Having cardiac surgeons, interventional cardiologists, and other specialists routinely collaborating on a team that is dedicated to pulmonary artery reconstruction has been the key to our success,” says cardiac surgeon Peter Chiu, MD.

Why MAPCAs and ToF are complex

When a child is born with ToF with pulmonary atresia and MAPCAs, their pulmonary valve is blocked or missing. Out of necessity, their body develops MAPCAs as “detour” blood vessels to carry blood to the lungs. While these vessels help at first, they often become too narrow or deliver too much blood, leading to serious problems for the heart and lungs.

The condition can differ significantly in each child. Some children may have only a single MAPCA; others have several. MAPCAs often arise from the aorta but they can also come from any artery. And their small size poses challenges: Affected pulmonary arteries can be 1 millimeter in diameter or smaller.

“This is a complex and variable form of heart disease,” says interventional cardiologist Brian Quinn, MD, who along with Chiu leads the team. “No two patients are the same, and each child’s anatomy presents unique challenges that require an individualized approach.”

A ‘marathon’ surgery that includes a ‘test drive’

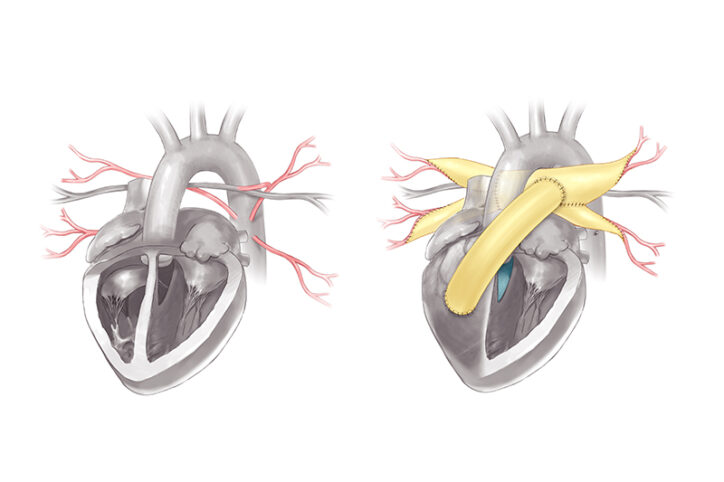

The center of treatment is unifocalization. In a procedure that can last as long as 20 hours, surgeons carefully join MAPCAs and a child’s natural pulmonary arteries and reconstruct them into a single, functional pulmonary artery system. “It’s like an ultra-marathon,” Chiu says of the operation.

Midway through the operation, the surgical team tests whether the reconstructed pulmonary arteries can support normal blood flow. Known as an interoperative flow study, the test uses a separate perfusion line from a heart-lung bypass machine to gradually increase blood flow so that surgeons can see if the arteries are robust enough for unifocalization to be completed in one stage. “It’s like taking the pulmonary arteries out for a test drive,” Chiu says.

If the pulmonary arteries aren’t ready to handle full blood flow, the team places a small conduit between them and the right ventricle to protect the arteries from high blood pressure. In these cases, a child may need to have pulmonary artery rehabilitation, a catheterization procedure performed by Quinn and his cardiology colleagues. About six months later, a child will usually have a second operation that places a larger conduit and closes the ventricular septal defect that’s associated with ToF.

“It is one of the most technically demanding surgeries we perform,” Chiu says. “But by working as a team, we can give these children the best possible chance for a healthier future.”

Focusing on care today and tomorrow

Care involves more than unifocalization. The pulmonary artery reconstruction team uses advanced imaging and catheter-based procedures to guide surgical planning and support recovery. 3D models, CT scans, and detailed catheterization studies allow the team to map out a patient’s pulmonary arteries, which often look and behave like a maze.

“Carefully connecting the vessels in the right order and along the correct pathways is an intricate and demanding process,” Quinn says, “but it is essential to designing the most effective repair.”

Quinn and Chiu believe their team is in a position to provide effective care for each child, but they still want to find new and better ways to treat the condition.

“This is a field that must continue to evolve,” Quinn says. “What we are doing today may look different from what we will be doing 18 months or five years from now. Our team is always working to improve long-term outcomes and enhance quality of life.”

If you have a patient who might benefit from unifocalization, please contact the Department of Cardiac Surgery.

Related Posts :

-

After surgery for heart condition tetralogy of Fallot, James is all joy

Warriors come in all shapes and sizes. Some even smile. In the Irvine family, the lead warrior is a happy ...

-

From South Africa to Boston: Kyleigh's four-year search for good heart health

Kyleigh Kista had three open-heart surgeries in just the first 18 months of her life. But instead of progressing, her ...

-

Knowing what life is worth: I am an adult heart patient and much more

Most of the children showed off a favorite toy. Some brought items that were meaningful to their family or culture. ...

-

Letters from the heart: “Life will be better”

Children with congenital heart disease (CHD) have much to think about as they undergo tests, try medications, and face possible ...