The clot thickens: Kellie Machlus, PhD

Part of an ongoing series profiling researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Platelets are the bandages of our blood, forming clots when we sustain an injury. Yet little is known about how they’re made, and there are no drugs that can immediately and directly trigger their production. Boston Children’s Hospital researcher Kellie Machlus, PhD, (@theclotthickens) couldn’t believe this at first.

“It’s crazy that there’s nothing we can do to acutely raise platelet counts,” she says. “You literally have to get platelets from another person.”

Machlus, 38, is a pioneer in this mysterious, under-explored area of biology. She hopes to provide better options for people who have lost platelets or have a blood disorder and cannot make enough.

An alluring medical mystery

Fresh from studying blood clotting biochemistry as a PhD student, Machlus was inspired by a conference talk by Joseph Italiano, PhD, in the Vascular Biology Program at Boston Children’s.

“Joe showed these beautiful videos of platelets being born,” says Machlus. “I thought, ‘I want that.’”

She joined Italiano’s lab, and he gave her an overview of how cells called megakaryocytes make platelets. She asked what triggers the process. His answer: “We have no idea.”

Machlus resolved to figure it out. “That complete absence of knowledge was so alluring to me.”

She soon learned that many companies have tried — and failed — to make platelets. Scientists have made megakaryocytes from stem cells, but haven’t been able to get them to make platelets.

Exploring platelets and megakaryocytes

Opening her own lab in 2020, Machlus decided to study inflammatory disorders like colitis and lupus, which naturally raise platelet counts.

“My idea is to learn from the body,” she says. “We’re taking a zoomed-out view of situations where platelets increase and trying to figure out what’s going on.”

Studying a mouse model of colitis, Machlus found that inflammation prompted platelets to produce a factor called CCL5 that spurs megakaryocytes to make platelets. She further found that during inflammation, platelets dispatch little bubbles called vesicles to the bone marrow, sparking production of megakaryocytes and, indirectly, platelets.

They’re crazy cells, that’s what drew me in. Everything you find out about them is new and interesting.”

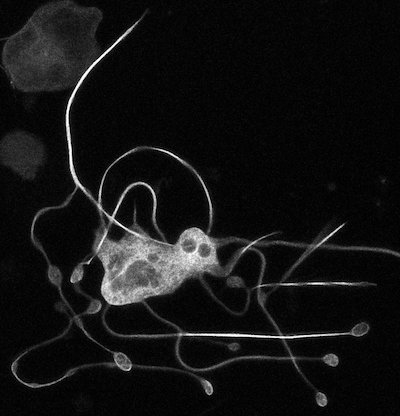

Machlus and her colleagues are also making their own megakaryocytes from donor bone marrow, then watching as some of them form platelets. Megakaryocytes are challenging to study because of their unusual biology — they can have up to 32 sets of chromosomes.

“They’re crazy cells, that’s what drew me in,” says Machlus. “Everything you find out about them is new and interesting.”

Bone marrow in a dish

To better glimpse platelet formation, Machlus has taken an exciting step, helping create the first-ever bone marrow “organoids.”

The 3D, jelly-bean-sized organoids mimic the bone marrow’s biology, including supporting tissue and adjacent blood vessels. The team can expose them to chemicals like CCL5 or even plasma from a patient with colitis to see if platelet production increases.

“I think this is going to blow the field apart,” says Machlus. “We can start asking new and exciting questions.”

Another recent study explored how diet affects platelet production — with fascinating results.

Mentoring a new generation

Aside from her groundbreaking science, Machlus is known for her passions for mentoring, building communities of scientists, and keeping women in science, including her trainees.

“What the next generation does is so important,” she says. “I brought my entire lab to a conference, and it was the best feeling.”

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, conferences were cancelled and research came to a standstill. Machlus sprang into action, creating Blood and Bone, a virtual seminar series.

“I made a Google spreadsheet, posted it on Twitter, and emailed 50 people asking them to spread the word,” she recounts. “In the end, we hosted more than 200 scientists giving seminars. Connecting people is one of my greatest joys in life.”

Read more profiles of Boston Children’s researchers.

Related Posts :

-

A true hero’s journey: How a team approach helped Wolfie overcome pancreatitis

Wolfgang, affectionately known as “Wolfie,” is a bright and energetic 7-year-old with a quick wit and a love for making ...

-

“A setback for a comeback”: Brody perseveres with Paget-Schroetter Syndrome

Baseball has been part of Brody Walsh’s story from the very start. Now 19 and a college sophomore, Brody pitches ...

-

Tough cookie: Steroid therapy helps Alessandra thrive with Diamond-Blackfan anemia

Two-year-old Alessandra is many things. She’s sweet, happy, curious, and, according to her parents, Ralph and Irma, a budding ...

-

Unique data revealed just when Mickey’s heart doctors could operate

When Mikolaj “Mickey” Karski’s family traveled from Poland to Boston to get him heart care, they weren’t thinking ...