Naloxone on demand: Shining a light to reverse opioid overdose

Overdose deaths from fentanyl and other opioids are at record highs in the U.S. Naloxone, if delivered soon after an overdose, is proven to be life-saving. It binds to the same brain receptors that opioids use, thereby blocking opioids’ effects. A naloxone nasal spray (Narcan) is now available over the counter, but there are still problems with access.

The lab of Daniel Kohane, MD, PhD, at Boston Children’s Hospital has developed an alternative: an injectable system that releases naloxone on demand. Its proof-of-principle study, involving mice intoxicated on high doses of morphine, appears in the journal NanoLetters.

A naloxone ‘sleeper cell’

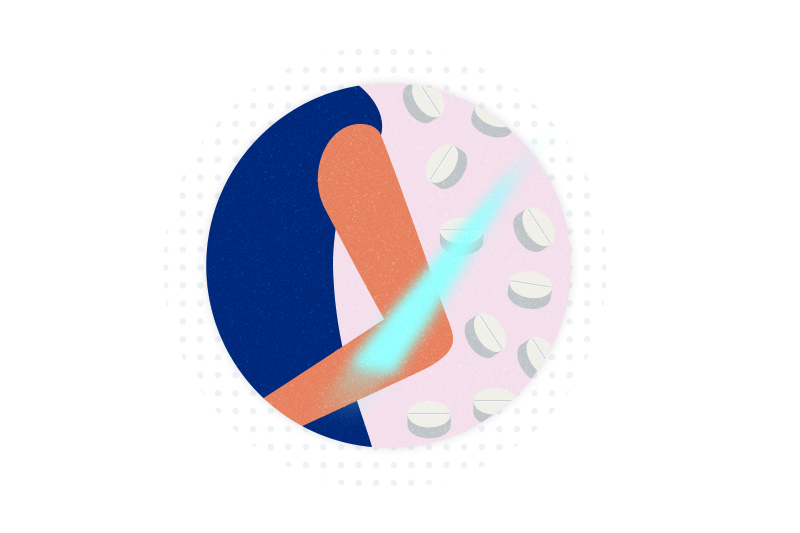

The concept is simple. A person at risk for overdosing (like a habitual opioid user) would periodically get an injection of nanoparticles containing naloxone in their arm or wrist.

“You would go to a clinic and they would inject it just below the skin,” says Kohane, who directs the Laboratory for Biomaterials and Drug Delivery. “It’s in you, so you can’t lose it.”

The particles would be formulated to be activated only by blue light — specifically, light with a wavelength of 400 nanometers. Users would carry a blue light source on their person — inside a special piece of jewelry, a watch, or medic alert bracelet, for example. If they overdose, they or someone else would shine the light on the coin-sized spot where the nanoparticles were injected, releasing naloxone into their bloodstream.

Reversing morphine’s effects

Building on their experience with on-demand local anesthetics, Kohane’s team, led by Wei Zhang, PhD, (now at the University of Pittsburgh), attached naloxone to a polymer material considered safe for humans, using coumarin, a light-sensitive molecule. While bound up with the polymer, the naloxone remains inert. Blue light breaks the bond to coumarin, freeing the naloxone.

In intoxicated mice, the system reversed morphine’s effects when the light was held over the injection site for two minutes — evidence that the released naloxone got to the brain. One subcutaneous naloxone injection was enough to revive mice in several overdose incidents over a 10-day period.

“It was important to us that naloxone could be triggered more than once, because opioids sometimes last longer in the system than naloxone, and sometimes people need more than one dose of naloxone,” Kohane explains.

Scaling up to humans

The system continued to counteract morphine up to a month after injection, though the effects diminished slightly. The team hopes to engineer the system to last a full three months and trigger naloxone release multiple times. Ultimately, their goal is to take it from mice to humans.

“As you try to move things into use in humans, you find all kinds of new problems,” Kohane cautions.

Because the system is on-demand, people with the “implantable antidote,” as he calls it, would still be able to take opioids if needed for pain relief after surgery or injury or for treatment of opioid use disorder, he adds. “You want narcotics to be able to work when you need them for clinical reasons.”

For more information on this technology, contact Greg Baker, PhD, Director of Business Development in Boston Children’s Technology & Innovation Office.

Explore projects in the Kohane Lab.

Related Posts :

-

High numbers of youth report using prescription opioids in the past year

A new analysis of data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health finds a surprisingly high prevalence of ...

-

Opioid alternative? Taming tetrodotoxin for precise painkilling

Opioids remain a mainstay of treatment for chronic and surgical pain, despite their side effects and risk for addiction and ...

-

As COVID-19 fuels opioid deaths, researchers look to create an anti-opioid vaccine

A project that began one year ago at Boston Children’s Hospital to develop an anti-opioid vaccine is starting to ...

-

Gold particles and light could melt venous malformations away

Venous malformations — tissues made up largely of abnormally shaped veins — are often difficult to treat, especially when located in sensitive ...