Lead exposure remains a problem for some children

Lead poisoning has been with us since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. But it wasn’t until the late 1970s that strong laws were passed to reduce lead in the environment. And 40+ years later, a large national study still finds evidence of possibly harmful lead exposure in young children, especially those living in low-income areas and in older housing.

Dr. Marissa Hauptman, of the Pediatric Environmental Health Center at Boston Children’s Hospital, partnered with Quest Diagnostics, one of the largest reference clinical laboratories in the U.S., to collect the data. Her findings were published today in JAMA Pediatrics, accompanied by an editorial.

Of the 1.1 million U.S. children under age 6 who were tested, half (50.5 percent) had detectable levels of blood lead (1.0 microgram per deciliter or higher). And almost 2 percent had elevated levels considered to be a risk to health (5.0 µg/dL or higher). Both percentages were higher for children who had public insurance, for those living in low-income zip codes, and for those living in homes built before the 1950s, when lead paint was still being used.

“We are still living with the effects of ‘legacy lead’ that was put in our environment decades ago,” Hauptman says. “While children’s lead levels have come down steadily since the 1960s, there’s still no known safe level of lead exposure. On a population level, we know that lead exposure impairs children’s neurologic development, especially executive-level brain functions, attention, and hyperactivity, although there may not be a recognized deficit in every child.”

A brief history of environmental lead exposure

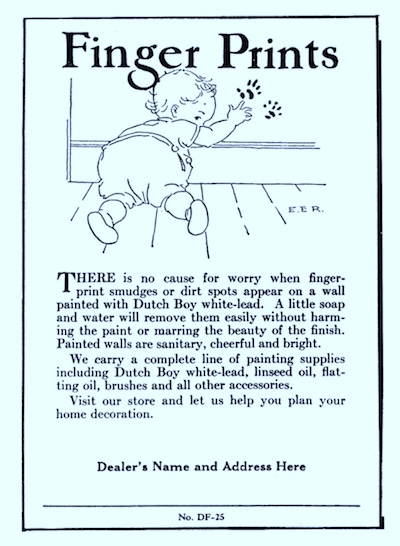

Lead paint became common in homes in the late 19th century. Lead made paint faster-drying, more durable, and moisture-resistant. But babies and young children began developing acute lead poisoning after ingesting paint chips flaking off windows, doors, and cribs. With the advent of automobiles, lead was added to gasoline to prevent “engine knock,” and it spewed into the air.

Boston Children’s Hospital has been at the forefront of documenting the harms of lead exposure. In the 1940s, Drs. Elizabeth Lord, a child psychologist, and Randolph Byers, a child neurologist, tracked 20 children who had been discharged as “cured” from acute lead poisoning. As they reported in 1943, all but one had persistent learning disabilities when they reached school age.

In 1979, another Boston Children’s study, led by Herbert Needleman, MD, linked high blood lead levels to IQ deficits in children. (First- and second-graders in Chelsea and Somerville donated baby teeth for the study.) And in 1987, Dr. David Bellinger of Boston Children’s led a study that documented harms from prenatal lead exposure.

But as documented in this review article, public policy lagged behind the science. Sometimes parents, or poverty, were blamed for lead poisoning’s effects. But eventually, the research led to a prohibition on the use of lead paint and helped accelerate the removal of lead from gasoline. Definitions of maximum safe lead levels became increasingly stringent, from 60 μg/dl in the 1960s to 5 μg/dl today.

Getting the lead out

Toxic levels of lead exposure are much less common today. But as the Flint water crisis reminds us, lead is still in the environment, and risks from lead paint remain in older homes.

Dr. Hauptman notes that 29 percent of children identified as having detectable lead were age 3 and older. “If children still have pica (ingesting items that aren’t food), as is common in children with autism, they could be at risk beyond age 1 or 2,” she says. “We need to continue to test for lead.

“The fact we’re still talking about lead in 2021 indicates that we need to invest in public health infrastructure and make sure families, pregnant women, infants, and children are as safe as possible,” she adds. “We need to invest more in our housing stock and not rely on residents and landlords to mitigate lead hazards. In Massachusetts, only 10 to 15 percent of homes have ever been inspected for lead.”

If you live in New England and think your child is being exposed to lead or other toxins, contact the Pediatric Environmental Health Center at Boston Children’s at 1-617-355-8177. The Center evaluates children with suspected exposures and provides treatment, such as chelation, as necessary.

Learn more about the Pediatric Environmental Health Center at Boston Children’s Hospital

Related Posts :

-

COVID-19 pandemic may put kids at risk for accidental poisonings

In the effort to keep kids safe from the new coronavirus, families could be unwittingly putting them at risk for ...

-

Racism is a health issue: How it affects kids, what parents can do

Racism has once again gained national attention. Following the deaths of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor, people around ...

-

COVID-19 exposed health inequities. These doctors let people know.

What’s a doctor to do when social issues make their patients sick? Traditional medicine can treat disease, but most ...

-

Many childhood injuries are preventable if you know the risks

As the seasons change, Dr. Lois Lee can predict that certain types of injuries will appear in the Emergency Department ...