The COVID-19 vaccine: Why some people of color hesitate

The COVID-19 pandemic has been especially hard on people of color. In addition to higher rates of infection, serious illness, and death, many Black and Latino communities have experienced profound economic hardship and increased anxiety and depression during the pandemic. Against this backdrop, the COVID-19 vaccines developed by Pfizer and Moderna might seem like great news. But many people of color aren’t so sure.

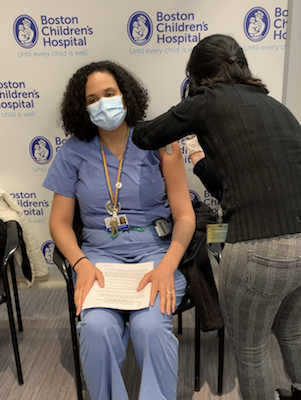

“There are many historical reasons why people of color may feel hesitant about the COVID-19 vaccine,” says Dr. Alexandra Epee-Bounya, clinical chief of Boston Children’s at Martha Eliot. The medical establishment has a history of mistreating people of color. One of the most notorious examples is the Tuskegee syphilis experiment. Researchers withheld treatment from Black men with syphilis so they could observe what happened when the disease was allowed to take its course. Though penicillin became the standard treatment for syphilis in 1947, the deceptive study continued until 1972.

A more recent example came to light in late 2020. A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine reported possible racial bias in testing of the pulse oximeter. The device measures oxygen levels by passing beams of light through a patient’s finger. Researchers found that the device, originally tested on mostly white subjects, was far less accurate in diagnosing respiratory distress in people with darker skin.

Given this backdrop, Drs. Epee-Bounya and Frinny Polanco Walters, a physician in the Division of Adolescent/Young Adult Medicine understand why many people of color look at the COVID-19 vaccines with a wary eye. They also hope their patients’ families will consider getting vaccinated anyway.

“COVID-19 has been very hard on Black and brown communities,” says Dr. Polanco Walters. “The vaccines are our hope to put an end to this pandemic, but people need to have their questions answered.” Below, the two physicians address some of the reasons people give for not wanting to get the vaccine.

Concerns and myths about the COVID-19 vaccine

The vaccines were developed too fast.

The COVID-19 vaccines were developed and authorized for use much more quickly than any other vaccine in history. This was possible in part because scientists around the world poured their time, expertise, and resources into finding a vaccine that could stop the worldwide pandemic. This does not mean they cut corners, however. “In reviewing how the vaccines were developed and tested, I did not find anything that made me doubt their safety,” says Dr. Epee-Bounya.

And the science of vaccine development has improved dramatically in recent decades. Dr. Epee-Bounya compares COVID-19 vaccines to smartphones. The idea that you would have a computer that could fit in your pocket would have seemed impossible 15 years ago. “When you think about how much technology has progressed, it makes sense that we could have safe, effective vaccines for COVID-19 in under a year.”

I’m worried about side effects.

Some people have mild side effects from the COVID-19 vaccines, which is the case with many vaccines. Side effects such as a sore arm, body aches, headache, and low-grade fever affect some people more than others, but typically only last a day or two.

I got the vaccine for me, I got it for my patients, and I got it to help bring an end to this pandemic that’s causing so much loss and suffering.”

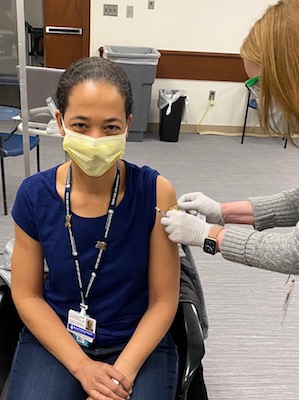

Frinny Polanco Walters

It’s true that a very small number of people have had serious allergic reactions to the vaccine. “Unfortunately, this has been blown out of proportion,” says Dr. Polanco Walters. The number of serious allergic reactions is tiny compared to the number of people vaccinated so far. And anyone who gets the vaccine is monitored for 15 to 30 minutes in case they need medical care. “When you consider what you’re getting — 95 percent protection against a deadly virus — the minimal risk is well worth it,” says Dr. Epee-Bounya.

Other people are getting vaccinated, so I don’t have to.

This reasoning relies on herd immunity, a point at which so many people are immune to a given disease, it stops spreading. Based on the highly infectious nature of COVID-19, experts now estimate that 90 percent of the population needs to be immune to achieve herd immunity. If everyone waits for everyone else to get vaccinated, we will never reach that point.

I’ll wait and see if the vaccine is really safe.

Dr. Epee-Bounya understands why people feel hesitant. “But I hope they will heed this call to action,” she says. “So much of what has happened to us for the past year has been beyond our control. Finally, there’s an action we can take — getting vaccinated — to bring this pandemic to an end.”

A way out of this mess

As pediatricians, Drs. Epee-Bounya and Polanco Walters have seen the terrible impact COVID-19 has had on patients and families. They’ve seen children devastated by the loss of a relative and parents who lost their jobs struggling to feed their families. After some hesitation, once they felt satisfied with the answers to their questions, they both got vaccinated this winter.

“I got the vaccine for me, I got it for my patients, and I got it to help bring an end to this pandemic that’s causing so much loss and suffering,” says Dr. Polanco Walters.

Learn more about COVID-19 vaccination.

Related Posts :

-

Study highlights the severity of acute necrotizing encephalopathy in kids with the flu

For most children, influenza (flu) usually means unpleasant symptoms like a fever, sore throat, and achy muscles. But for a ...

-

Model enables study of age-specific responses to COVID mRNA vaccines in a dish

mRNA vaccines clearly saved lives during the COVID-19 pandemic, but several studies suggest that older people had a somewhat reduced ...

-

Making pediatric health equity research truly equitable: An EDI review process

A burgeoning number of studies are examining pediatric health equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI). But if not done right, health ...

-

Will people accept a fentanyl vaccine? Interviews draw thoughtful responses

In 2022, more than 100,000 people died from opioid overdoses in the U.S., according to the National Center for Health Statistics. ...