Why do some people get severe COVID-19? The nose may know

The body’s first encounter with SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind COVID-19, happens in the nose and throat, or nasopharynx. A new study in the journal Cell suggests that the first responses in this battleground help determine who will develop severe disease and who will get through with mild or no illness.

Building on work published last year identifying cells susceptible to the virus, a team of collaborators at Boston Children’s Hospital, MIT, and the University of Mississippi Medical Center comprehensively mapped SARS-CoV-2 infection in the nasopharynx. They obtained samples from the nasal swabs of 35 adults with COVID-19 from April to September 2020, ranging from mildly symptomatic to critically ill. They also got swabs from 17 control subjects and six patients who were intubated but did not have COVID-19.

“Why some people get more sick than others has been one of the most puzzling aspects of this virus from the beginning,” says José Ordovás-Montañés, PhD, of Boston Children’s, co-senior investigator on the study with Bruce Horwitz, MD, PhD of Boston Children’s, Alex Shalek, PhD, of MIT and Sarah Glover, DO, of the University of Mississippi. “Many studies looking for risk predictors have looked for signatures in the blood, but blood may not really be the right place to look.”

COVID-19’s first battlefield: the nasopharynx

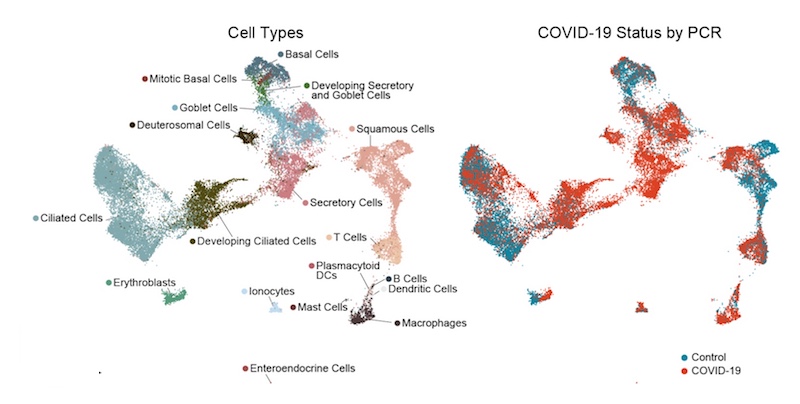

To get a detailed picture of what happens in the nasopharynx, the researchers sequenced the RNA in each cell, one cell at a time. (For a sense of all the work this entailed, each patient swab yielded an average of 562 cells.) The RNA data enabled the team to pinpoint which cells were present, which contained RNA originating from the virus — an indication of infection — and which genes the cells were turning on and off in response.

It soon became clear that the epithelial cells lining the nose and throat undergo major changes in the presence of SARS-CoV-2. The cells diversified in type overall. There was an increase in mucus-producing secretory and goblet cells. At the same time, there was a striking loss of mature ciliated cells, which sweep the airways, together with an increase in immature ciliated cells (which were perhaps trying to compensate).

The team found SARS-CoV-2 RNA in a diverse range of cell types, including immature ciliated cells and specific subtypes of secretory cells, goblet cells, and squamous cells. The infected cells, as compared with uninfected “bystander” cells, had more genes turned on that are involved in a productive response to infection.

A failed early immune response

The key finding came when the team compared nasopharyngeal swabs from people with different severity of COVID-19 illness:

- In people with mild or moderate COVID-19, epithelial cells showed increased activation of genes involved with antiviral responses — especially genes stimulated by type I interferon, a very early alarm that rallies the broader immune system.

- In people who developed severe COVID-19, requiring mechanical ventilation, antiviral responses were markedly blunted. Most notably, their epithelial cells had a muted response to interferon, despite harboring high amounts of virus. At the same time, their swabs had increased numbers of macrophages and other immune cells that boost inflammatory responses.

“Everyone with severe COVID-19 had a blunted interferon response early on in their epithelial cells, and were never able to ramp up a defense,” says Ordovás-Montañés. “Having the right amount of interferon at the right time could be at the crux of dealing with SARS-CoV-2 and other viruses.”

Boosting interferon responses in the nose?

As a next step, the researchers plan to investigate what is causing the muted interferon response in the nasopharynx, which evidence suggests may also occur with the new SARS-CoV-2 variants. They will also explore the possibility of augmenting the interferon response in people with early COVID-19 infections, perhaps with a nasal spray or drops.

Having the right amount of interferon at the right time could be at the crux of dealing with SARS-CoV-2 and other viruses.”

“It’s likely that, regardless of the reason, people with a muted interferon response will be susceptible to future infections beyond COVID-19,” Ordovás-Montañés says. “The question is, how do you make these cells more responsive?”

Carly Ziegler, Vincent Miao, Andrew Navia, and Joshua Bromley of MIT and Harvard; Anna Owings of the University of Mississippi; and Ying Tang of Boston Children’s Hospital were co-first authors on the paper. Funders include the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative DAF, the National Institutes of Health, the New York Stem Cell Foundation, the Richard and Susan Smith Family Foundation, the AGA Research Foundation, the Food Allergy Science Initiative, The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard.

Explore COVID-19 research at Boston Children’s Hospital

Related Posts :

-

New research sheds light on the genetic roots of amblyopia

For decades, amblyopia has been considered a disorder primarily caused by abnormal visual experiences early in life. But new research ...

-

Thanks to Carter and his family, people are talking about spastic paraplegia

Nine-year-old Carter may be the most devoted — and popular — sports fan in his Connecticut town. “He loves all sports,” ...

-

No limitations: How Flora found answers for MOG antibody disease

Flora Ringler’s fifth birthday didn’t turn out as she had hoped. She and her family were vacationing in ...

-

Genetic causes of congenital diarrhea and enteropathy come into focus

Congenital diarrheas and enteropathies are rare and devastating for infants and children. Treatments have consisted mainly of fluid and nutritional ...