Against all odds: Mila’s unique mutation, and her own custom drug

Ed. note: Mila passed away in February 2021, at age 10. The Mila’s Miracle Foundation continues to work to pave a pathway for personalized treatments. The FDA recently released a draft guidance on testing custom drugs such as Mila’s in patients.

As a baby and toddler, Mila was healthy, active, and — in some ways — even advanced for her age. She began speaking before she turned 1, went skiing for the first time at age 2, and was a fearless climber on furniture and rock walls.

However, after she turned 3, Mila developed a strange gait, with her feet turning in.

“We had her checked and were told that was normal and that she would outgrow it,” says Julia, her mother.

But more was to come. “At around 4 years old, we noticed that Mila would have her face pushed down against the books she was reading,” Julia says.

Mila began frequently tripping, falling, and hitting her head in the playground because she didn’t notice things at the edge of her vision. Mila’s loss of vision became painfully clear when she watched her favorite movie, Frozen, with her gaze pointed away from the TV screen. Her father, Alek, shone a light in her eyes and saw little response.

“Just before her sixth birthday, it was obvious that this was very serious and progressive,” Alek says. “Since she couldn’t see, she couldn’t walk by herself, so we started holding her so she could walk assisted.”

Mila’s language was also slipping away.

“She went from speaking perfectly to having fragments of a sentence to speaking just three, two, and then one word,” Julia says. “And then eventually, she lost her last word, which was ‘mommy.’”

‘Make the most of your time with Mila’

At age 6, seeing Mila’s steep decline in vision, walking, and talking, her parents took her to the local hospital emergency room. Mila spent a week in the hospital. Doctors diagnosed her with Batten disease, a rare, progressive genetic disorder that affects the brain and nervous system. Children with Batten disease eventually lose their ability to communicate and function independently, and ultimately become unresponsive, often dying before their teens.

“Pretty much every doctor I spoke with said, ‘Make the most of your time with Mila, because there really is no hope right now,’” says Julia. “I cut out all images I had in my head of Mila growing up, having a boyfriend, going to college, or having a job. It was too painful for me.”

‘We’re going to work on this’

Despite her clinical diagnosis, Mila’s genetic diagnosis was incomplete. Batten disease is recessive, so it requires two mutations. One, inherited from Alek, was easy enough to find in the CLN7 gene. But the second mutation, which would have come from Julia, couldn’t be found with standard genetic testing. They had reached the end of the readily available testing options — with only half an explanation for Mila’s symptoms.

Time wasn’t on their side. Julia and Alek were concerned not just for Mila, but also for her brother Azlan, then 3 years old. Would he develop Batten disease too?

A friend of Julia’s belonged to a physician moms group on Facebook and re-posted a plea Julia had made on social media. Could someone sequence Mila’s entire genome to find the hidden mutation — and quickly?

The post was forwarded to Dr. Cindy Lien, an internal medicine physician in Boston, who showed it to her husband, Dr. Timothy Yu, a neurologist in the Boston Children’s Hospital Division of Genetics and Genomics. Yu runs a research lab that has extensive experience using whole genome sequencing, and has developed methods to find unusual mutations that most clinical labs are unable to pick up.

“Dr. Yu reached out to me the next day and said, ‘Can you send me a sample of your daughter’s blood? We’re going to work on this,’” Julia says.

Finding Mila’s mutation

That was in January 2017. By February, Yu’s team had whole genome sequencing (WGS) results in hand. WGS covers a person’s entire DNA sequence — the complete genetic instruction set. This includes “noncoding” segments, not covered by most clinical testing, that are responsible for how strongly genes are expressed and how proteins may be assembled. Scientists are only just beginning to understand these noncoding DNA regions — which some call the “dark matter” of the genome.

A noncoding region is where Dr. Yu and colleagues found Mila’s second mutation. A rogue piece of genetic code had jumped into Mila’s genome, into a stretch of noncoding DNA embedded in the CLN7 gene. As a result, Mila’s cells were misreading the genetic instructions and making a truncated, non-functional protein.

“Dr. Yu called us and said, ‘We have found the mutation. It’s something extremely unusual,” says Julia. “Then he said, ‘There’s one more thing. We have an idea of how we might be able to help Mila.'”

Designing a treatment

Dr. Yu could not promise a cure or even an improvement in Mila’s condition, but her mutation turned out to have a potential repair. Dr. Yu believed that his team could design a piece of artificial genetic code, called an antisense oligonucleotide (ASO), to silence the rogue bit of genetic code that was disrupting CLN7. If successful, this would allow the gene to be assembled properly, enabling Mila’s cells to make normal copies of the protein — and hopefully function normally again.

Without the protein, Mila’s cells were progressively dying. But with treatment, perhaps further loss could be prevented.

To test this idea, Dr. Yu’s lab designed several oligonucleotides customized to Mila’s mutation and added them to her cells in a dish. Eventually, they came up with one that looked promising — and named it milasen.

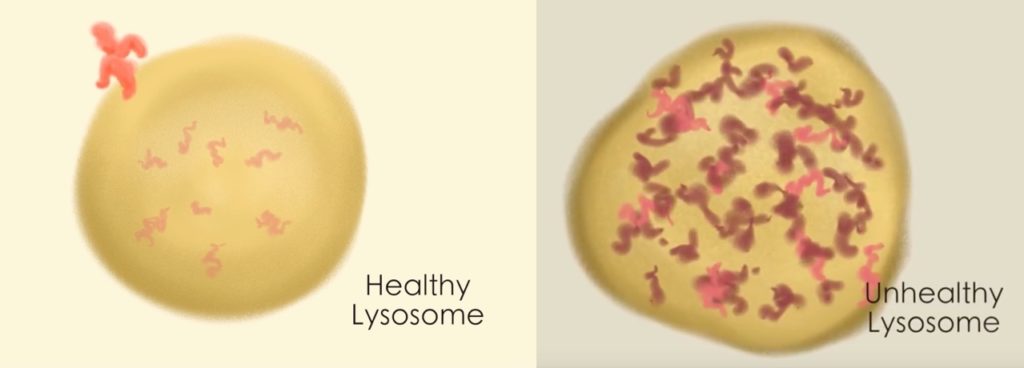

In experiments in the fall of 2017, Dr. Yu’s lab first showed that milasen repaired the assembly of CLN7 protein in Mila’s cells. With collaborators at Northwestern University, they then showed that it restored healthy function of her lysosomes, the “trash bins” that cells use to recycle their waste. In Batten disease, the lysosomes don’t work, get clogged up, and begin to overflow. The cell makes more and more lysosomes, but those fill up, too.

“Eventually the cell is overwhelmed, so it no longer functions and eventually dies,” says Dr. Yu. “When we introduced our drug into Mila’s cells, the number of lysosomes shrunk and the amount of trash spilling over into the hallway, so to speak, also shrunk.”

Taking a chance

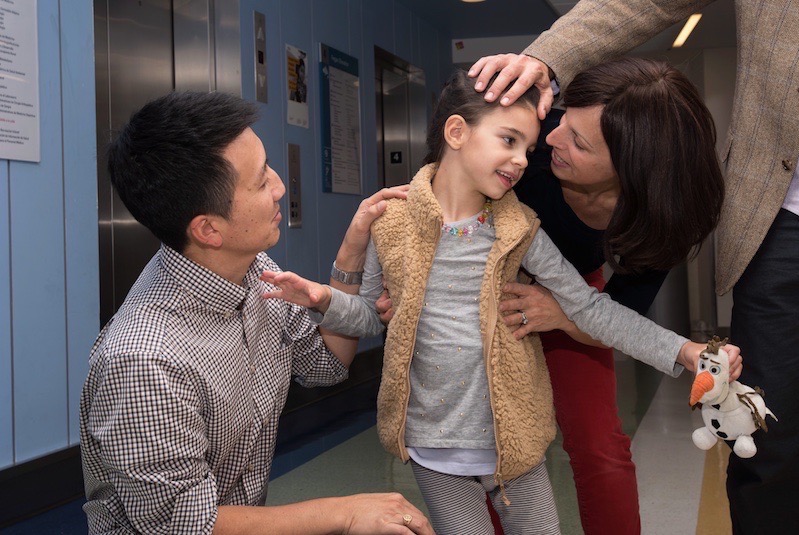

It was now time for Dr. Yu and his colleagues at Boston Children’s to decide: Did Mila have a chance of benefiting from milasen, or was it too late to help her? In October 2017, shortly before turning 7, Mila flew from Colorado with her family to be evaluated by Dr. Yu and other physicians at Boston Children’s. The physicians agreed that milasen would be worth trying.

“Mila had lost a lot,” says Dr. Yu, “but you could see she had a lot of personality. She was alert, interacting meaningfully with her parents, and could walk while holding onto a stroller. We all felt that preserving what Mila had would be a success.”

The next step was to approach the hospital, as well as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Would they approve testing a brand-new drug, never given to humans, in a single patient? Multiple departments and committees at the hospital weighed in, including the bioethics committee. Ultimately, all said yes. Without treatment, Mila would continue to decline.

Shooting for the moon

Translating genetic discoveries to actual treatments usually takes decades. Dr. Yu’s team pulled it off in less than a year, using Boston Children’s funds, Dr. Yu’s own research funds, and support from Mila’s Miracle Foundation, an organization formed by Julia soon after Mila’s initial diagnosis.

During the fall of 2017, Dr. Yu worked with partners in industry to design a manufacturing and toxicology strategy. Together with colleagues in genetics, neurology, anesthesia, and the Institutional Center for Clinical Translational Research, he worked out the logistics of Mila’s spinal injections and how she would be evaluated. On January 19, 2018, the FDA sent a letter allowing Mila’s treatment to proceed — an exciting moment for everyone.

On January 25, 2018, Mila arrived at Boston Children’s for extensive pre-treatment evaluations, including neurologic workups, a brain EEG, and physical therapy evaluations. To her delight, Dr. Olaf Bodamer, associate chief of the Division of Genetics and Genomics, came in to meet her.

“One of Mila’s very last words was Olaf, because she loves the snowman Olaf in Frozen,” says Julia. “I told her, ‘That snowman Olaf with a carrot nose? He’s a doctor too!’ And she burst into laughter.”

Mila’s first treatment

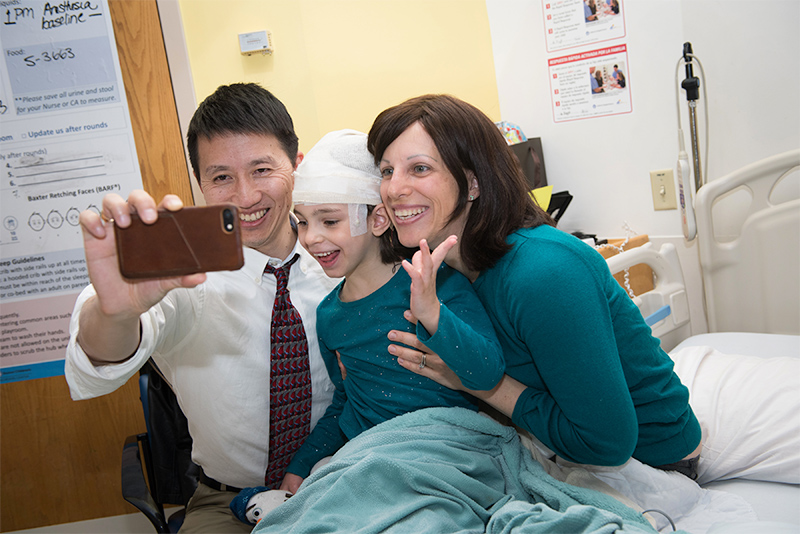

Mila received her first test dose of milasen on January 31, 2018. Dr. Charles Berde of the Department of Anesthesiology administered the drug.

“About two hours after Mila went under anesthesia, I said to myself, ‘Oh my gosh, right now Mila’s brain is absorbing a drug made just for her. And it could stop her disease,’” says Julia. “I went from having no hope to thinking ‘maybe, just maybe, she has a chance.’”

Mila’s team monitored her closely as her milasen dose was gradually increased every two weeks over the first five months of 2018. She then went on a maintenance schedule, receiving the drug every three to four months, and eventually every two months.

Watching and waiting

Only time will tell what will happen long term. But Batten disease is usually one of relentless decline. Mila’s seizures, which had been occurring 20 to 30 times a day, came down to zero to 10 per day. They’re also much shorter and less severe, going from 1 to 2 minutes to a few seconds each. Dr. Yu and colleagues reported these early findings October 9 in The New England Journal of Medicine, and continue to collect data and fine-tune her therapy. She is now able to receive her treatments at her home hospital in Colorado.

After about two months of treatment, Julia began noticing positive changes. Mila could hold her body and head upright while standing and taking steps (though she still needs support), and she occasionally walks up stairs with alternating feet (also with support). She has fewer issues with swallowing than before her treatment began, her hands are more often un-clenched, and her legs bend more smoothly. She seems to be trying hard to talk and occasionally says a word or two.

“Mila has good days and bad days,” says Julia. “But overall, she has been pretty stable with some important improvements since starting her treatment. She isn’t responsive to her favorite songs and stories as often as she was last year, which has been difficult to watch. However, after each dose we see her responsiveness return temporarily.

“We knew that Mila was quite progressed when she began her treatment and that this was a long shot,” Julia adds. “And we knew that her treatment had never been done before — she was the first. We don’t know what lies ahead for Mila, but every little sign of stability and improvement keeps us fighting for her.”

Beyond Mila

The creation of milasen, in less than a year, could signal the beginning of a revolution in how genetic conditions are treated. Boston Children’s hopes to learn from Dr. Yu’s process for developing milasen — from diagnosis to drug synthesis and treatment — so that in the future, similar cases might be addressed here and elsewhere, one patient at a time. However, many questions and obstacles remain to be addressed before widespread adoption of this approach.

“Mila’s treatment has proven that this is possible,” says Julia. “Our foundation hopes to continue playing a big role in paving this new treatment path.”

Learn more about the development of milasen and the science behind it.

Related Posts :

-

Promising advances in fetal therapy for vein of Galen malformation

In 2024, Megan Ingram* of California and her husband were preparing for the birth of their third child when a 34-week ...

-

A case for Kennedy — and for rapid genomic testing in every NICU

Kennedy was born in August 2025 after what her parents, John and Diana, describe as an uneventful pregnancy. Soon after delivery, ...

-

The hidden burden of solitude: How social withdrawal influences the adolescent brain

Adolescence is a period of social reorientation: a shift from a world centered on parents and family to one shaped ...

-

The journey to a treatment for hereditary spastic paraplegia

In 2016, Darius Ebrahimi-Fakhari, MD, PhD, then a neurology fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital, met two little girls with spasticity ...