Too many blood cells: Probing a blood cancer’s genetic origins

At age 7, Meredith Shah began having debilitating migraine headaches. “I would have trouble seeing and shapes were blurry,” she recalls. “It was really painful.” Over time, the frequency and intensity of the headaches escalated. Her parents, Heidi and Nil, sought the help of multiple specialists. But they received few answers, other than an indication she had abnormal platelet counts.

Myeloproliferative neoplasms, in which the body makes too many blood cells, are caused by non-inherited mutations. Why, then, do they run in families?

“As a physician, it was challenging not to think about the worst possible scenarios,” says Heidi. “Does she have a tumor? Are we going to get a cancer diagnosis? I was very concerned it was potentially life threatening.”

In 2012, after nearly two years without a diagnosis, Heidi and Nil brought Meredith to Boston Children’s Hospital from their home in central Massachusetts for further testing.

“Bringing her to Boston Children’s was laden with emotion,” says Nil. “We were waiting at the precipice of where it could lead. That uncertainty was devastating.”

Mysterious headaches: Clue to a bone marrow disorder

Vijay Sankaran, MD, PhD, a hematology fellow at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, recommended that Meredith have a bone marrow biopsy. That unlocked the mystery behind her excruciating headaches. Meredith had a mutation in the JAK2 gene, an essential diagnostic marker of bone marrow disorders called myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs).

A pediatrician might notice that blood counts are a little off. Headaches, fatigue, itchiness, sweating, and other general symptoms can go undiagnosed for many years unless someone suspects MPNs and tests for one of the known mutations.”

– Vijay Sankaran

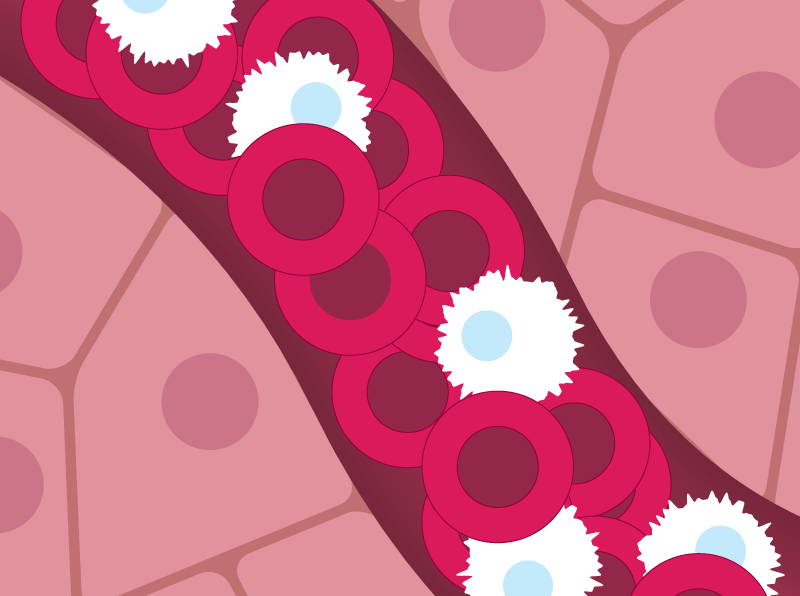

MPNs are blood cancers in which the body makes too many blood cells — red cells, white cells, or platelets. Complications vary depending on which cell types are over-produced. But in general, MPNs pose an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease, and a dramatically increased risk for leukemia — 10- to 20-fold over a patient’s life. Unfortunately, many people go years without a proper diagnosis.

“A pediatrician might notice that ‘blood counts are a little off,’” says Sankaran. “There may be headaches, fatigue, itchiness, sweating, and other general symptoms. These can go undiagnosed for many years unless someone suspects MPNs and tests for one of the known mutations, like we did with Meredith.”

Meredith’s biopsy not only identified the JAK2 mutation, but also increases in the number of precursor cells that make platelets and red blood cells.

“We didn’t know what the arc of the disease would be, whether there was a chance that the mutation could progress in such a way that it would run out of control and potentially be cancerous,” says Nil.

Untangling the genetics of myeloproliferative neoplasms

Over the past 15 years, MPNs have been found to arise from a spontaneous, non-inherited mutation in a blood-forming stem cell. The cell makes copies of itself, which go on to create an excess of blood cells, the type of cell depending on the type of mutation. Mutations in several different genes have been documented, most commonly JAK2.

“But there’s been one mystery that’s been plaguing the field,” says Sankaran, who is also affiliated with the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. “If you have a myeloproliferative disorder, your first-degree relatives are at five- to seven-fold risk of also having an MPN.”

What is causing MPNs to run in families? Sankaran and colleagues launched a large-scale genome-wide association study involving 3,797 people with MPNs and 1,152,977 controls.

That study, published today in Nature, identified a new set of genetic risk factors. These factors predispose people to acquiring new MPN-causing mutations in their blood stem cells.

Read more stories from Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center.

Overall, the team found 17 inherited variants in different regions of the genome, 10 of them not previously known. Delving further, they found evidence suggesting that these variants cause too many blood stem cells to be made. Variants in two genes, CHEK2 and GFI1B, seemed especially important.

“People with more blood stem cells are more at risk of acquiring a mutation that can cause an MPN,” explains Sankaran. “Now that we have a list of genetic variants, we can go through them systematically and look at the underlying biology to understand how they affect blood stem cells.”

More from the Broad Institute: Studies reveal mutations that boost blood stem cell growth and increase leukemia and heart disease risk

A deeper understanding of MPNs

While these studies are at an early stage, Sankaran believes these inherited risk factors offer an opportunity to better understand why some patients like Meredith develop MPNs. Ultimately, the findings may inform the development of new interventions.

“Now that we know what inherited factors predispose to MPNs, we can assess an individual’s risk based on how many of the variant regions they carry in their genome,” says Sankaran. “If you have an inherited risk factor, you tend to get MPNs at a younger age, as Meredith did. Children with MPNs tend to have stronger genetic risk factors and a younger age of onset.”

Today, nearly eight years after Meredith’s MPN diagnosis, the 17-year-old is healthy. Her headaches are managed with daily baby aspirin, and her platelets and blood cell counts are monitored with regular lab work. Despite her uncertain future, the family is grateful that Sankaran has given them real certainty around Meredith’s diagnosis.

“Each piece of information Dr. Sankaran learns, he presents to us with competence, clear communication, and respect for human emotion,” says Heidi. “Even though we’ve never stopped walking on eggshells completely, I know we are in the right hands.”

Learn more about myeloproliferative neoplasms.

Related Posts :

-

A case for Kennedy — and for rapid genomic testing in every NICU

Kennedy was born in August 2025 after what her parents, John and Diana, describe as an uneventful pregnancy. Soon after delivery, ...

-

The journey to a treatment for hereditary spastic paraplegia

In 2016, Darius Ebrahimi-Fakhari, MD, PhD, then a neurology fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital, met two little girls with spasticity ...

-

New research paves the way to a better understanding of telomeres

Much the way the caps on the ends of a shoelace prevent it from fraying, telomeres — regions of repetitive DNA ...

-

New research sheds light on the genetic roots of amblyopia

For decades, amblyopia has been considered a disorder primarily caused by abnormal visual experiences early in life. But new research ...