CHIP-ing away at health and medicine for 25 years: A look back

In 1994, when CHIP was formed, the dotcom boom was just dawning. iPhones and social media (except for the earliest versions) were more than a decade away. Bill Clinton was president.

Isaac Kohane, MD, PhD, had just completed a fellowship in endocrinology at Boston Children’s Hospital under the mentorship of Joseph Majzoub, MD. He wanted to pursue a research project: creating a web-based electronic health record (EHR). He believed health information is more powerful when it’s shared, and that patients should own and control their own health data, with software tools to assist them.

“Most records were still on paper,” Kohane recounted at CHIP’s 25th anniversary symposium last month (highlights below). “I could get my bank balance and withdraw money all over the world, but the only place I could get my diagnosis was at the doctor’s office.”

Kohane’s vision included applying artificial intelligence (AI) to managing and learning from patients’ health data. AI was then facing cuts in research funding, after a series of publicized failures. But Kohane was undeterred.

“Zak was very hard to constrain,” Majzoub recalled. “It was like watching someone tied to a comet.”

If we build it they will come

Kohane’s project led to the chartering of CHIP, then called the Children’s Hospital Informatics Program. Jim Fackler, MD, was co-leader, and Ken Mandl, MD, MPH, in the Division of Emergency Medicine, became the third CHIP faculty member in 1995. Part of CHIP’s charter was to provide rigorous education in medical informatics, and to nurture collaborations with industry and other research centers.

They were very much alone those first few years.

“Information at that time was a one-way street,” Kevin Churchwell, MD, Boston Children’s president and chief operating officer, reminded the symposium audience. “Care was more about the physician than the patient.”

“Many of CHIP’s ideas influenced the development of the health care system,” noted Mandl. “But many took a long time to take root.”

Taking on the EHR

CHIP’s earliest project, with Peter Szolovits, PhD, and others in the MIT Lab for Computer Science, proposed a “Guardian Angel” that would act as “A Personal Lifelong Active Medical Assistant.” Its manifesto, released in 1994, stated:

Current health information systems are built for the convenience of health care providers and consequently yield fragmented patient records in which medically relevant lifelong information is sometimes incomplete, incorrect, or inaccessible. We are constructing information systems centered on the individual patient instead of the provider, in which a set of “guardian angel” software agents integrates all health-related concerns… about an individual.

In 1998, Mandl and Kohane launched a personally controlled health record, PING, later called Indivo. The first platform of its kind, it placed the patient at the center of medical computing. This video describes it nicely:

Indivo formed the basis of personally controlled health record systems rolled out by Intel and Walmart (Dossia), Microsoft (HealthVault), and Google (Google Health) in 2007-2008. Those products didn’t last, but Mandl, now CHIP’s director, sees hope in a new generation of patient-centered computing enabled by CHIP’s technologies.

Apple’s new iPhone Health app is a case in point, putting patients in control of their health data at hundreds of hospitals. It runs on a platform developed by Mandl and Kohane’s team — an open programming interface known as SMART, launched in 2010.

SMART enables consumer- and physician-facing health apps to seamlessly and securely exchange information with the health care system. It incorporates Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR), a new standard for facilitating information exchange between healthcare systems. (Interoperability is a required component of health information technology under the U.S. 21st Century Cures Act.) Today, more than 75 apps run on SMART, offering everything from care coordination to blood pressure measurement to population health.

Genomics and big data

CHIP’s computational science also made an impact on the burgeoning field of genomics. In 2000, CHIP researchers led by Kohane and Atul Butte, MD, PhD, (now at USCF) introduced the concept of “relevance networks” — groups of genes whose expression profiles are highly predictive of one another. Going beyond the single-gene approach, these networks of genes turning on and off have provided a new understanding of the genetics of disease and how biological systems are regulated. Kohane also introduced the concept of the incidentalome — unintentional genetic findings uncovered by genomic testing for something else.

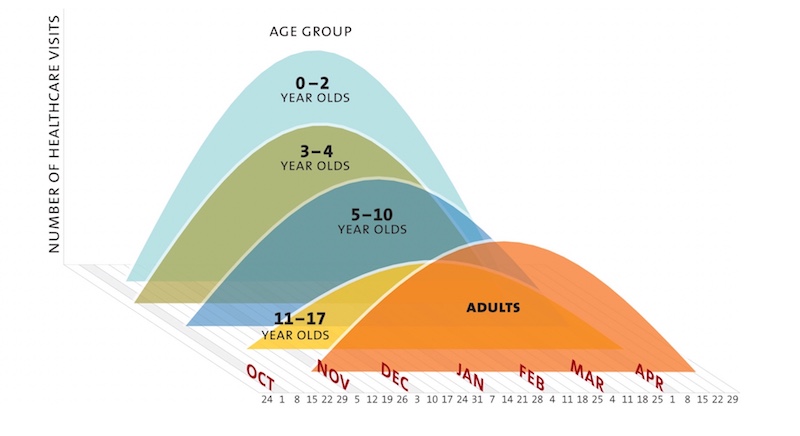

John Brownstein, PhD, now Boston Children’s chief innovation officer, joined CHIP in 2005. He quickly demonstrated the power of computational science when applied to health data. Analyzing visits for flu-like respiratory illness, Brownstein and Mandl demonstrated that preschoolers are the first to present in large numbers with flu, helping drive the epidemic. That led the CDC to change its vaccination recommendations, extending flu shots to 3- and 4-year-olds.

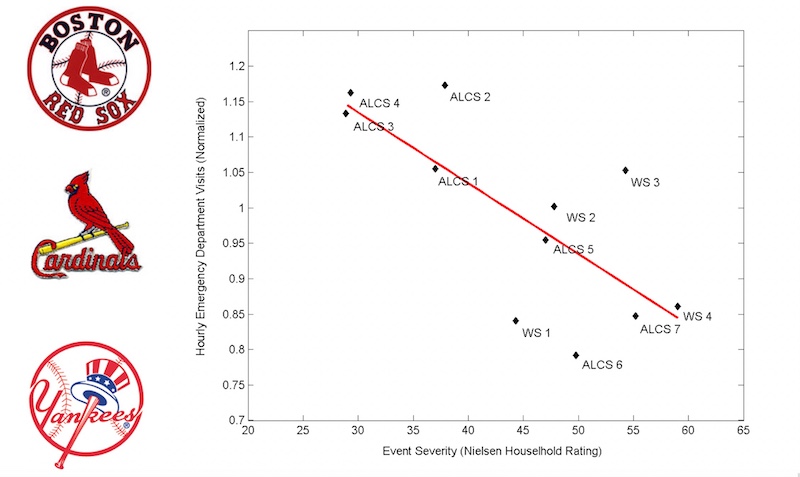

In another project, Brownstein, Mandl, and CHIP researcher Ben Reis, PhD, looked back at the historic 2004 baseball postseason. They tracked hourly visit rates at six Boston-area emergency departments (EDs) against TV Nielsen ratings of Red Sox postseason games. When the Sox were losing, few people tuned in, and ED visits were about 15 percent higher than expected. But then the tide turned, and TV viewership surged. During World Series Game 4 — the first World Series win by the Red Sox since 1918 — ED visits dipped about 15 percent below the expected volume.

Health surveillance, predictive medicine, and decision support

These seminal projects foreshadowed HealthMap, established in 2006 as a freely accessible, automated information system for tracking and visualizing global disease outbreaks. HealthMap taps both formal government surveillance data and informal sources like online chats, local newspaper reports, and social media. It provided early warning signs of the 2009 H1N1 (swine flu) pandemic and the 2014 Ebola outbreak, to name just a couple. Just in the past month, it gave a more complete picture of the epidemic of vaping-related pulmonary disease.

The 2000’s also saw the advent of cTAKES (clinical Text And Knowledge Extraction System), a natural language processing system that gathers unstructured information from clinicians’ notes in EHRs. CHIP faculty member Guergana Savova, PhD, led its development.

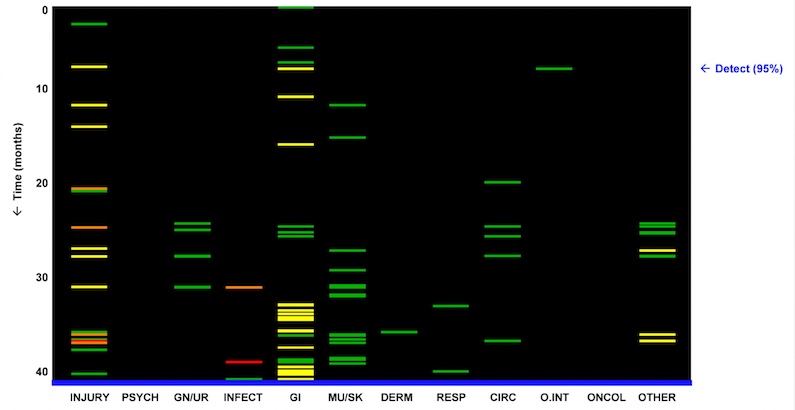

With a 2009 study, Reis pioneered the field of predictive medicine. Using data solely from electronic health records, he identified medical visit patterns suggestive of domestic abuse. See below, where each colored bar represents a diagnosis recorded in a patient’s chart during the four years before the abuse diagnosis. (Green bars denote low probability of abuse; yellow, medium; red, high.) As the blue “detect” arrow points out, the system could have sounded an alert as early as 34 months before the abuse was medically recognized.

Another predictive tool, called POPP, brings CHIP-created machine learning to the ED. POPP predicts which patients presenting at triage will ultimately be admitted, helping hospitals improve their operations.

So what’s next?

Now called the Computational Health Informatics Program, CHIP today has 31 faculty members, affiliated faculty, and industry fellows. Its newest faculty member is a sixth-generation mentee of the program. Some current trainees weren’t even born when CHIP was founded. CHIP has spun out multiple startups, including ACT.md, a cloud-based complex care platform; Epidemico, a population health-tracking company acquired by Booz Allen Hamilton; Circulation, which partners with Uber and Lyft to provide non-emergency medical transportation; and Abcuro, which uses informatics to design new therapies for patients.

As for the next 25 years, symposium participants made a variety of predictions. That patients will demand much more information that they currently get from current patient portals. That clinicians will embrace assisted intelligence to help them at the bedside. That hospitals will become “care traffic controllers” and less of a physical presence, as patient-facing wellness apps keep people out of the hospital. That clinical trials will wane as new tools enable researchers to ask clinical questions of large databases.

Ultimately, not everyone agreed on what 2044 would look like. But one prediction seems clear: CHIP will be at the forefront of posing the questions and building solutions. “Seeing how long many of our projects needed to take root, it is not too soon to strategize for 25 years from now,” says Mandl.

Learn about more Boston Children’s research.

Related Posts :

-

Advancing global health: Using AI to detect heart disease in children

In many low- and middle-income countries, pediatric cardiologists can’t help children with congenital heart conditions because of a critical ...

-

AI-enabled medical devices are burgeoning, but many haven’t been tested in children

Medical devices that incorporate artificial intelligence and machine learning are proliferating. In 2013, the FDA approved fewer than 10 such devices; by 2023, ...

-

Finding epilepsy hotspots before surgery: A faster, non-invasive approach

Neurosurgery for patients with drug-resistant epilepsy requires locating the precise brain areas that are generating the seizures. Typically, patients undergo 7 ...

-

‘Zero place for mistakes’: Taking fetal surgery to the next level with simulation

The highly complex interventions involved in fetal surgery require exceptional skill, training, and experience. Beyond the procedures themselves, these surgical ...