When community is as important as the science: Olúmídé Fagboyegun

In his short, prolific neuroscience career, Olúmídé Fagboyegun has always sought community. It’s served him well, from his years at community college in Maryland to his PhD work in the Stevens Lab at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Landing in Maryland from his native Nigeria at age 15, Fagboyegun found he had to repeat part of high school. He did, and then attended Anne Arundel Community College, where the school’s emphasis on mentorship and teaching hooked him in.

“They were focused on how to best help students succeed, especially students who were nontraditional,” he says. “These students are often overlooked on the academic path.”

A science scholarship enabled him to finish his final semester without having to work an extra job. He graduated in 2018 as class valedictorian.

Curiosity about astrocytes

Moving on to pursue a bachelor’s in Biochemistry at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, Fagboyegun soon found research-oriented communities, including the Meyerhoff Scholars and U-RISE programs. He got funding to attend the Annual Biomedical Research Conference for Minoritized Students, exposing him to graduate programs and research scientists.

That led to internships at the University of Minnesota and Washington University in St. Louis, where he investigated Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease. He began thinking deeply about science and learning about the non-lab-bench aspects of being a scientist, such as writing. Meanwhile, his scientific interests were fast evolving away from biochemistry.

“As an undergraduate, I developed a very deep interest in glial cell biology,” he says.

Glial cells, which intermingle with neurons in the brain, used to be viewed as mere supporting cells to neurons, he explains. But they’re now known to be players in their own right with multiple roles. Fagboyegun wanted to know more about them — especially astrocytes, star-shaped glial cells that help maintain the blood-brain barrier and influence the formation of synapses between neurons, among other functions.

That strong sense of curiosity, instilled by his parents in Nigeria, has drawn him to labs that are pushing the boundaries of neuroscience.

Taking on big ideas

Fagboyegun’s first rotation as a graduate student with Harvard Medical School’s Program in Neuroscience was in the Boston Children’s Hospital lab of Maria Lehtinen, PhD. While Lehtinen doesn’t study glia, she studies other kinds of non-neuronal cells in the brain. Her specific interest is the cells of the choroid plexus, a little-known tissue in the brain’s fluid-filled cavities that secretes factors regulating brain development, immunity against infection, and more.

“Maria is amazing, a very engaged mentor who’s interested in the nitty-gritty but also in the big ideas,” says Fagboyegun. “We were very aligned.”

The liking is mutual. “He’s always eager to test new ideas and think outside the box,” Lehtinen says. “We would have loved to have him join the lab.”

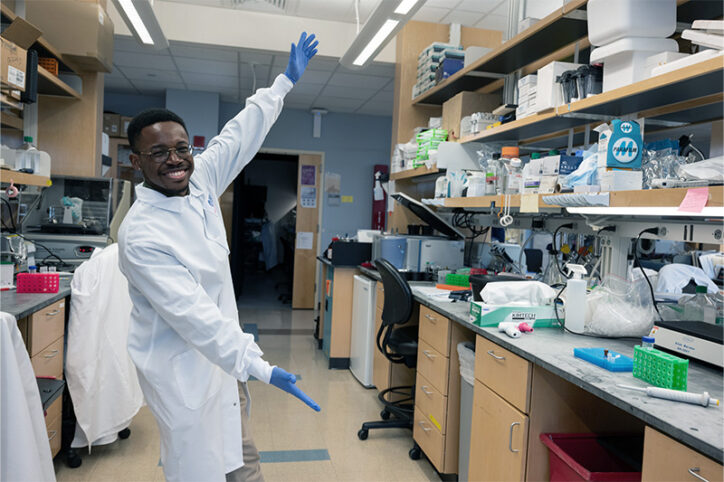

That honor has gone to the lab of Beth Stevens, PhD, which focuses on glial cells and neuro-immune interactions during healthy development and disease. Fagboyegun joined the lab in 2022 and quickly found a welcoming home.

“When I have a wild, out-there idea, I go to Beth and she says, ‘Oh, yeah, this sounds really exciting.’”

A new fellowship community

He and Stevens were recently awarded a Gilliam Fellowship through the Howard Hughes Medical Institute as a mentee-mentor pair. Fagboyegun will receive $53,000 in annual support for his dissertation research, with Stevens as his advisor.

“I’ve always had my eye on this fellowship,” he says. “It funds people who are not just doing good science, but are also interested in changing the landscape of diversity, equity, and inclusion in the biomedical sciences. The emphasis is on bringing everyone together, often, to interact and brainstorm and help each other navigate challenges.”

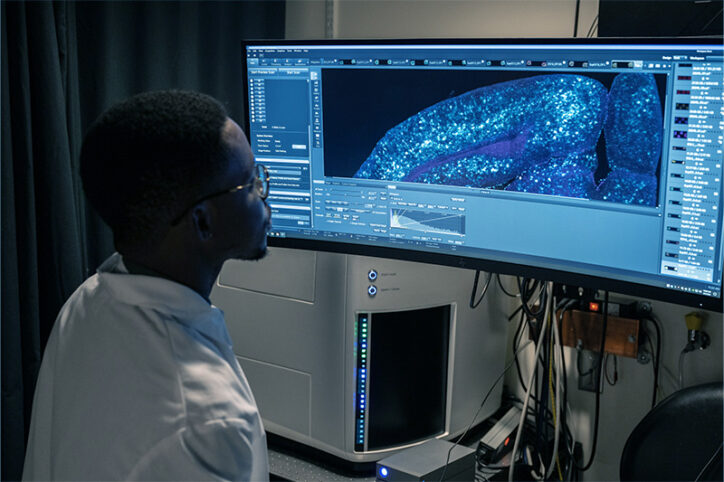

His dissertation topic is “Studying the cortical microenvironment.”

“Every cell in the body is surrounded by a matrix of sugars, proteins, and structural components that shape the way cells and organs function,” he explains. “I’m focused on trying to understand how interactions between cells and the matrix change across brain development, and how changes in the matrix influence how cells develop. The only reason I’m able to work on this is because Beth is open to new ideas in her lab.”

Stevens is thrilled to have Fagboyegun in the lab. “Olúmídé has built his research project from the ground up, highlighting features of astrocyte and glial biology that I might not have otherwise pursued,” she says. “He’s a leader and community builder whose enthusiasm for science, excellent communication skills, and kindness will make him a powerful role model.”

Building creativity

Fagboyegun is eager to pay it forward. The F.M. Kirby Neurobiology Center, of which the Stevens Lab is a part, has an initiative that brings students from Bunker Hill Community College to do research in its labs. He’s looking forward to serving as a mentor in the program next summer — a chance to come full circle.

“It requires understanding that people are coming from a lot of different places in life and appreciating the kinds of challenges people face when taking a nontraditional path,” he says.

In his spare time, Fagboyegun enjoys indoor rock climbing and blind wine tasting, where he’s found other communities. He also enjoys reading, especially fiction.

“When you read, you’re taking the perspective of the characters — it gives you a lens to appreciate the world,” he says. “Fiction is a really effective way to build creativity, which in science is very necessary.”

Read more profiles of Boston Children’s researchers and learn more about science at the Kirby Center.

Related Posts :

-

Two rising stars in kidney genetics: Nina Mann and Amar Majmundar

A healthy, functional kidney must maintain a delicate balance of water, nutrients, and electrolytes so it can properly filter the ...

-

The clot thickens: Kellie Machlus, PhD

Part of an ongoing series profiling researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital. Platelets are the bandages of our blood, forming ...

-

Unraveling the secret to attention, one brain cell at a time: Brielle Ferguson, PhD

In college, Dr. Brielle Ferguson was initially drawn to psychology. Witnessing the impact of schizophrenia on a family member, she ...

-

A global take on rare disease research: Maya Chopra, MBBS, FRACP

Several years ago, while working as a clinical geneticist at the Imagine Institute of Genetic Diseases in Paris, Dr. Maya ...