Printing a plan to resolve an athlete’s pain

Just days away from a complex hip surgery, Louise Atadja smiles and laughs. “I’m not really nervous at all. I feel like it’s the next thing on my to-do list, like we’re just checking off a box,” she says. “That’s the type of person I am — I make lists of what I have to do, so that’s how I’m thinking about it.”

Competing through pain

As a track star in high school and college, Louise was always playing through the pain — which mostly seemed to come from her knees. She decided to visit a doctor during her senior year of high school, when the pain became so bad that she couldn’t finish a cross-country race.

An MRI revealed she had very little cartilage left in her knees, but Louise refused to let it affect her collegiate track career. She underwent physical therapy while at Amherst College — still tormented by knee pain so significant she often couldn’t walk after track meets. While many athletes would call it quits, for Louise, the pain wasn’t enough to stop her from running.

“It should have,” she pauses for a moment, “it really should have. But it didn’t, because of my love for competing and my love for track.”

Planning for her potential

After graduating from Amherst with a degree in neuroscience and working as a medical researcher in Texas, Louise decided to seek a second opinion from Boston Children’s Hospital Orthopedic Center.

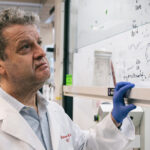

A previous MRI had revealed that Louise’s knee pain was actually the result of a combination of two conditions in her hip: hip impingement and hip dysplasia. These issues, plus the physical demands of an extensive track career, were causing more stress on her knees. So Louise met with Travis Matheney, an orthopedic surgeon and pediatric and young adult hip specialist at Boston Children’s.

“I think a lot of the reason I like Boston Children’s is that they’re more than a children’s hospital,” Louise explains. “They have a Child & Young Adult Hip Preservation Program and they’re trying to get me to the next stage. There’s still time to develop and grow, they know my potential as an athlete is still there.”

Matheney and his team developed a two-part plan. It would require two separate surgeries — one for each side of the hip — and involved 3-D printing Louise’s hip and femur using new technology offered by the Boston Children’s Simulator Program (SIMPeds).

By acquiring this 3-D printed model, Matheney was able to incorporate it into the pre-operative planning that is integral to any major orthopedic procedure. The model allowed him to better identify the rotation of the femur in Louise’s hip socket, informing whether his first move in surgery would be to fix the hip socket or work on her femur.

Revelations of a 3-D model

Once the hip and femur were printed, Matheney noticed something that hadn’t shown up in imaging. “When I lined the femur up with the pelvis model and moved it around, I started to get the impression that something else was happening,” Matheney recalls. “There was a very subtle extra prominence on the ball of the femur itself.”

Matheney realized that this anatomical anomaly might have been adding to Louise’s lack of motion and pain. He decided the best course of action would be to take a closer look inside the joint itself during surgery — a decision that normally isn’t made unless there is significant damage to the joint that can be seen in MRI.

During the pre-op appointment, Matheney handed Louise her very own hip and femur. “It was just an amazing experience,” she says. “I held my hip in my hands as Dr. Matheney pointed out what he was going to fix.”

Sticking to the plan

Louise described her moments before surgery as “just really nice and peaceful.” She said, “I trust God, I trust Dr. Matheney, and I trust the procedure. I know it’s all going to be just fine.”

And it was.

Now in recovery, Louise has progressed to being mobile on crutches. She’s even able to do her physical therapy exercises without pain. “Everything went according to plan,” she laughs. “That’s a new thing for my body.”

Matheney is grateful to have utilized the 3-D printed model in his surgical planning, even though he has performed this same surgery with great success in the past without a printed model. He believes that the detail he observed through using the model may have led to his correction improving Louise’s motion by an additional 5-10 degrees of rotation and flexion. As an avid athlete and runner, Louise is thankful for all the motion she can get.

She’s also thankful for the experience of having Dr. Matheney in charge of her care. “He’s been so accessible and so encouraging,” says Louise. “He knows that I have a life outside of surgery, and he’s trying to get me to the point of improving that part of my life.”

Louise is gradually improving her life outside of surgery through her own hard work. After her physical therapist heard she was a track athlete, he understood what had been motivating her to push through therapy so intensely — and then told her he’d be raising his expectations as a result. With her mindset of checking every box on the way to recovery, Louise is up to the challenge.

The journey forward

Louise’s lofty ambitions have now deeply rooted themselves outside the realm of athletics and track. She’s currently applying to medical school, and hopes to one day be a pediatric neurologist. After doing an observership at Boston Children’s during her junior year, Louise became fascinated with the idea of helping kids with neurological disorders find ways to succeed in school — an issue often brought up by their concerned parents. “I have this goal that at the end of the day, every kid should get to enjoy being a kid, no matter their sickness or disorder,” Louise says. “Because a life without recess is no life at all.”

With MCATs behind her and medical school on the horizon, Louise is completely focused on her recovery. In her last post-op appointment, Matheney was hopeful that she would be able to start walking ahead of schedule. That was welcome news to Louise.

But for her, walking is just the means to an end. “I’m super happy that I’ll be able to start running again,” she says. “I think I’m just excited to start being me again. I know there’s a lot of physical therapy and that second surgery in my future. But in my mind, that’s just another box to check.”

Learn more about Boston Children’s Child & Young Adult Hip Preservation Program.

Related Posts :

-

How a meniscal transplant made me a Boston sports fan

I was in kindergarten when my knee started popping and cracking. My parents and I didn’t know it at ...

-

Hard and beautiful at the same time: Five lessons of raising a medically complex child

When they learned they were expecting a baby, Michelle and Stephen Strickland were delighted. The South Carolina couple looked forward ...

-

3D imaging could become standard practice in orthopedics. Here’s how.

It took a trained eye to see the abnormality on the patient’s X-ray. There, hidden behind the acetabulum was ...

-

A safe, pain-specific anesthetic shows preclinical promise

All current local anesthetics block sensory signals — pain — but they also interrupt motor signals, which can be problematic. For example, ...