A ‘super’ new heart surgery for a super kid

When you’re the first person in the world to undergo a new type of heart surgery, you don’t have to use the procedure’s clinical name. You can give it any name you want, even your own.

That’s what 7-year-old Easton Schlein’s family has done. While his Boston Children’s cardiac surgery team calls the groundbreaking procedure a “reverse double-switch 1.5 ventricle repair,” at the Schlein home in North Carolina, it’s known simply as the “Super Easton.”

It’s a fitting tribute to Easton. His parents believe he’s nothing but super. With confidence, persistence, and a love for fun, he has made the best of not only several complex heart procedures, but also brain surgeries and more than 30 rounds of radiation treatment.

“He just he fights for everything he has,” says his mom, Julie. “He’s a pretty amazing kid.”

Finding another way

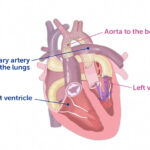

Three days after his birth at a local hospital, Easton had heart failure and was diagnosed with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS). It is a congenital heart defect (CHD) in which underdeveloped structures on the left side of the heart can’t effectively pump blood, causing breathing difficulties and other symptoms. As Julie and her husband, Marlin, processed the diagnosis, they also had to worry about Easton needing treatment for sepsis.

Once recovered from sepsis, Easton had three surgeries over the next six months — pulmonary banding and the Norwood and bidirectional Glenn procedures — in a process that would reconfigure his heart anatomy to allow the stronger right ventricle to perform the work of two ventricles. Once he reached 2 or 3, and if his heart matured to expectation, he could have the final procedure, the Fontan.

But during Easton’s treatment, a clinician mentioned that a few hospitals perform “new procedures” that strive for more than a single-ventricle anatomy. Following the success of the bidirectional Glenn, Julie and Marlin researched the cardiac surgery programs of those hospitals, including Boston Children’s. They heard from Dr. Sitaram Emani, director of Boston Children’s Complex Biventricular Repair Program, who studied Easton’s medical history. Dr. Emani told them Easton could someday be a candidate for biventricular repair, a complex procedure that creates a heart with two functioning ventricles. “We were excited,” Julie recalls. “That was going to be the next big step.”

A serious setback

But about three weeks before Easton’s first visit to Boston Children’s, he was unresponsive during an afternoon nap. Rushed to a local hospital, he was diagnosed with a brain tumor and a buildup of cerebrospinal fluid. Only 19 months old, he needed emergency surgery to remove the tumor and another procedure to place a shunt to drain excess fluid — and then palliative care and 33 rounds of radiation.

“It shut him down,” Julie says. “It took Easton about six months to relearn how to walk and talk, and another few years to learn to run and jump without stumbling. But he was determined to be here. He’s definitely a fighter. He loves life, and he doesn’t want to lose it.”

Making heart treatment history

After recovering from brain cancer, Easton got back on track with heart treatment. But Dr. Emani eventually informed the family that Easton’s heart wouldn’t handle two ventricles fully pumping. A Fontan procedure — at the time, the only alternative to biventricular repair — would better suit his anatomy.

But the day before Fontan surgery, Dr. Emani had a bold proposal. His team saw enough potential in Easton’s left ventricle to help circulation, so they wanted to forgo the Fontan and try a new procedure they had created for his condition. Easton would be the first in the world to have the “reverse” double-switch 1.5 ventricle repair as part of a strategy to surgically rehabilitate the left ventricle in patients with borderline left heart. In fact, he would be the first to ever have the procedure for any heart condition. His parents knew they had to approve the surgery.

“We weren’t 100-percent confident about him being first, but we were 100-percent confident we were trying to do the right thing,” Julie recalls. “We knew that if it didn’t work, it still could help other families who would be in our shoes.” More than that, they wanted to honor Easton’s desire to live. “We were willing to take risks in the hope he would get more time. We knew how much joy he brought to others. He’s got a unique personality. He loves to make people smile.”

Smiles, swimming, and soccer

Flash forward three years and a fully-recovered Easton keeps on smiling. A bit of a “jokester,” he makes his parents and siblings — 28-year-old Kaitlyn, 15-year-old Grayson, and 11-year-old Bryson — laugh. They cherish spending time with him. He runs, swims, and rides his bike without difficulty and no longer needs an oxygen tank he previously had to turn to nearly every time he caught a cold. He also enjoys cheering for the University of North Carolina Greensboro soccer team and occasionally running onto the field and high-fiving players before a game.

Medical history books might not refer to his procedure as the “Super Easton,” but his family won’t mind. They’re happy their superhero is finally healthy. “We had all these emotions with Easton being the first to go through that,” Marlin says. “It was a big leap. But we’re really thankful he is doing well and that the surgery has been able to help other children.”

Learn more about the Complex Biventricular Repair Program or request a second opinion.

Related Posts :

-

Experience and innovation create a safer type of heart surgery

The Eureka moment came the day before heart surgery. Easton Schlein wasn’t an ideal candidate for a full-scale surgical ...

-

From Pakistan to Boston: Faiz finally found help for his complex heart condition

Don’t let his shy smile fool you. In his hometown of Lahore, Pakistan, 6-year-old Muhammad Butt is known by ...

-

Saving baby Marcela: A mother’s mission to finally hold her daughter

The translations of this page are translated from English into another language using Google Translate, a third party tool. Please ...

-

To #SavePriyanshu: A father’s reach across the world to save his son

Any parent can relate: to the ends of the earth is just the beginning of how far you will go ...