Tuber locations associated with infantile spasms map to a common brain network

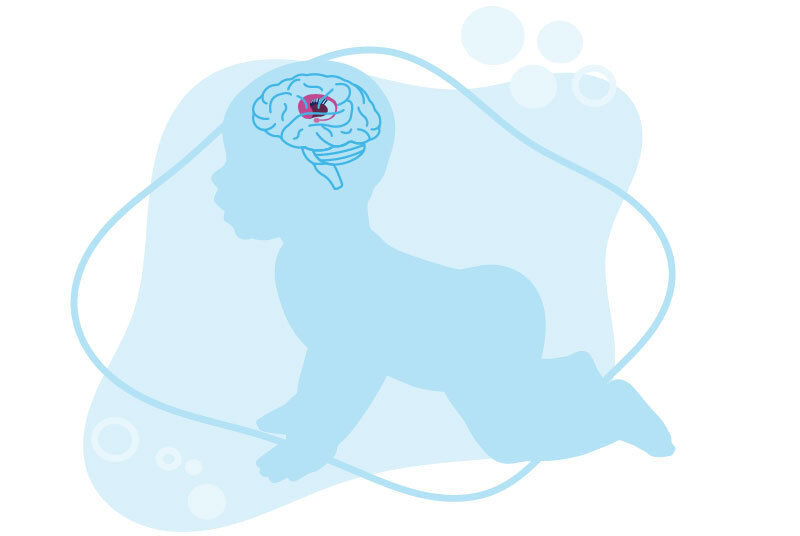

About half of all babies with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) develop infantile spasms, a type of epilepsy that can have serious long-term neurologic consequences. Infantile spasms occur more often in children who have more brain tubers — groups of cells that do not divide into normal neurons and brain cells — but we haven’t known if tuber location was important.

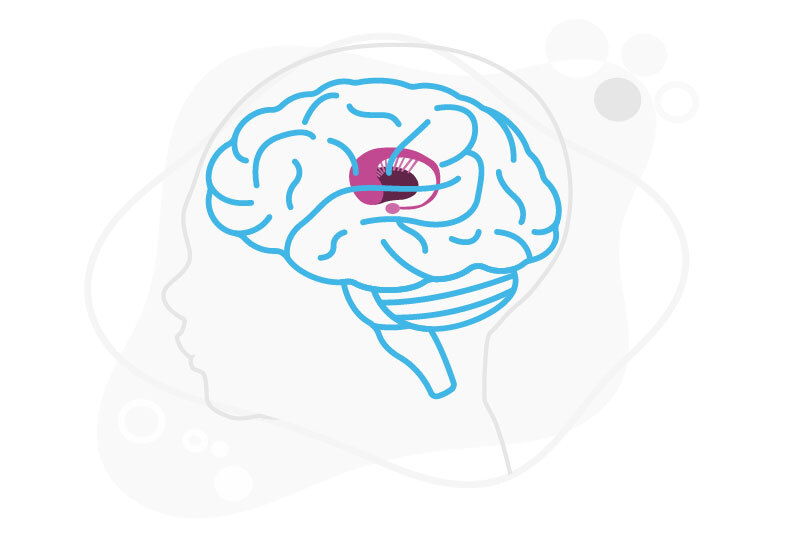

New research published in Annals of Neurology by Alexander Cohen, MD, PhD, and Jurriaan Peters, MD, PhD, of the Department of Neurology found that the risk of infantile spasms increases when tubers disrupt a brain network connected to the globus pallidus, a structure deep in the brain.

“Until now, there has been no clear reason why certain patients with TSC get this severe type of epilepsy and others do not,” says Peters. “Since spasms have a negative impact on the development of these children, we need to know who will develop spasms and see if we can find better ways to treat them.”

Tuber network converges on a deep brain structure

In their study, Cohen and Peters mapped the brain networks of 123 children with TSC, including 74 with infantile spasms and 49 without. “It turns out that patients with infantile spasms did not all have tubers in one particular location,” says Cohen. “But they all had tubers in one particular network across the brain.”

They discovered that 71 out of 74 children with TSC-associated infantile spasms (more than 95 percent) had tubers in parts of the brain connected to the globus pallidus. Children who did not have infantile spasms did not have tubers with this association.

Rather than only getting a seizure in one area, infantile spasms spread to the entire brain or large portions of it. “Knowing that the globus pallidus is involved provides a really good explanation for why the seizure moves so quickly to involve the whole body,” says Peters. “This area of the brain is a central “hub” for motor control.”

Identifying at-risk patients

TSC — and the location of individual tubers — can be diagnosed in babies before birth. Armed with this network information, physicians may be able to detect whether those tubers place a baby at increased risk for infantile spasms. These babies could then be treated with current drugs like vigabatrin; those whose tubers do not increase their risk of infantile spasms would be spared unnecessary treatment.

“If we can refine our analysis, we might ultimately be able to identify the so-called ‘spasmogenic’ tuber — the tuber that starts it all,” says Peters. “In that case, maybe one could surgically remove that tuber, and perhaps stop progression to infantile spasms.” Other non-invasive techniques, like transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) or transcranial direct current stimulation (TDCS) — which are generally fairly ineffective for treating the large-scale seizure of infantile spasm — might have more relevance.

“For decades, people have been trying to figure out why patients with a wide variety of brain lesions get seizures and spasms and others don’t,” adds Peters. “At least for babies with TSC, now we can say that these lesions actually have something in common; they all talk to the same area.”

Learn more about the Epilepsy Center at Boston Children’s

Related Posts :

-

Mending injured hearts: Lessons from newborns?

When the heart is injured, as in a myocardial infarction, the damaged heart muscle cannot regenerate — instead, scar tissue forms. ...

-

Exploring brain operations: Making decisions, snapping to attention, and forming memories

How do our brains snap to attention and orient us to the outside world — like when we’re sound asleep ...

-

The journey to a treatment for hereditary spastic paraplegia

In 2016, Darius Ebrahimi-Fakhari, MD, PhD, a neurology fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital, met two little girls with spasticity and ...

-

When diagnosis is just the first step: The Brain Gene Registry

Through advances in genetic sequencing, many children with rare, unidentified neurodevelopmental disorders are finally having their mysteries solved. But are ...