Failed cancer drug may extend life in children with progeria

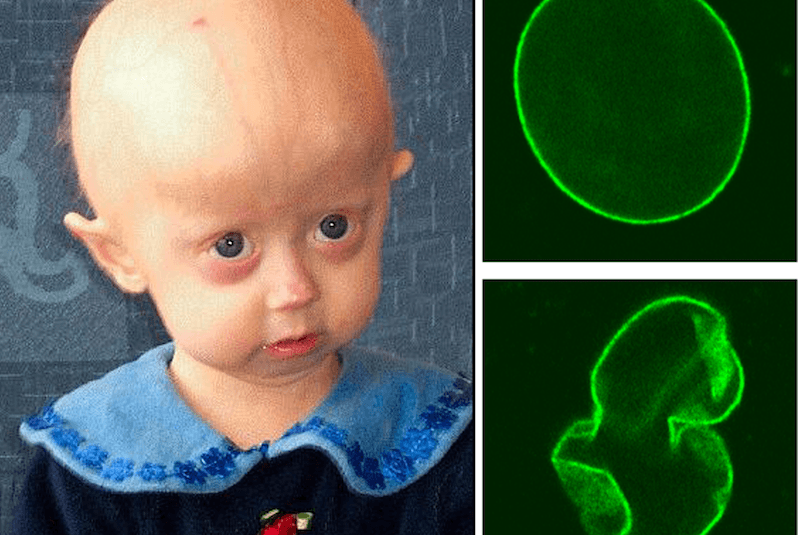

Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome, better known as progeria, is a highly rare genetic disease of premature aging. It takes a cruel toll: Children begin losing body fat and hair, develop the thin, tight skin typical of elderly people and suffer from hearing loss, bone problems, hardening of the arteries, stiff joints and failure to grow. They die at an average age of 14½, typically from heart disease resembling that of old age.

An observational study published yesterday in the Journal of the American Medical Association suggests that a drug called lonafarnib, originally developed as a potential cancer treatment, can extend these children’s lives.

“These results provide new promise and optimism to the progeria community,” said Leslie Gordon, MD, PhD, of Boston Children’s Hospital and The Progeria Research Foundation, which funded the study, in a press release. (Gordon, who was also lead study author, lost her son to progeria at age 17.)

Repurposing an experimental cancer drug

Children have been coming to Boston Children’s Hospital from all over the world to receive lonafarnib since 2007. That’s just four years after the gene that’s mutated in progeria was discovered, by a team led by Francis Collins, MD, PhD, now director of the National Institutes of Health, in collaboration with The Progeria Research Foundation. The mutation lead to an overabundance of a protein named progerin, which distorts the nucleus of the cell (as shown above) and blocks normal cell function.

Part of progerin’s toxic effect comes from attachment of a molecule called a “farnesyl group” to the protein. Lonafarnib blocks this attachment by inhibiting the enzyme farnesyltransferase.

Mark Kieran, MD, PhD, an oncologist with Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, had been testing lonafarnib in children with malignant brain tumors, since adding a farnesyl group also activates the cancer-causing Ras oncogene. While the drug failed as a cancer treatment, Kieran’s experience using it in children brought the Progeria Research Foundation to his door. Monica Kleinman, MD, medical director of the Medical/Surgical Intensive Care Unit at Boston Children’s Hospital, was co-investigator on the initial trials and is principal investigator for the current ongoing progeria trials at the hospital.

Reducing progeria mortality

In the first clinical trial results, reported in 2012, many of the 25 children treated with lonafarnib had improved weight gain, reduced blood vessel stiffness, improved bone density and flexibility, better hearing or some combination of these outcomes.

The new report presents mortality data from 258 children from six continents. The treated children received oral lonafarnib for a median of 2.2 years as part of clinical trials at Boston Children’s (the above trial and another begun in 2013). They were compared with untreated children from a natural history study. The two lonafarnib groups combined had 4 deaths among 63 children (6.3 percent mortality), while the match, untreated group of 63 children had 17 deaths (27 percent mortality).

The Progeria Research Foundation continues to fund other studies. “This study published in JAMA shows for the first time that we can begin to put the brakes on the rapid aging process for children with progeria,” said Gordon.

Some researchers believe progeria research could have lessons for the general population.

“While it’s a long way off, it’s possible that some of the same approaches that aim to treat children with progeria could slow the aging process for the rest of us,” Collins told the Boston Globe.

Related Posts :

-

In the genetics of congenital heart disease, noncoding DNA fills in some blanks

Researchers have been chipping away at the genetic causes of congenital heart disease (CHD) for a couple of decades. About 45 ...

-

The journey to a treatment for hereditary spastic paraplegia

In 2016, Darius Ebrahimi-Fakhari, MD, PhD, a neurology fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital, met two little girls with spasticity and ...

-

Microvillus inclusion disease: From organoids to new treatments

Microvillus inclusion disease (MVID) is a rare type of congenital enteropathy in infants that causes devastating diarrhea and an inability ...

-

When diagnosis is just the first step: The Brain Gene Registry

Through advances in genetic sequencing, many children with rare, unidentified neurodevelopmental disorders are finally having their mysteries solved. But are ...