Taking a targeted approach when leukemia comes back

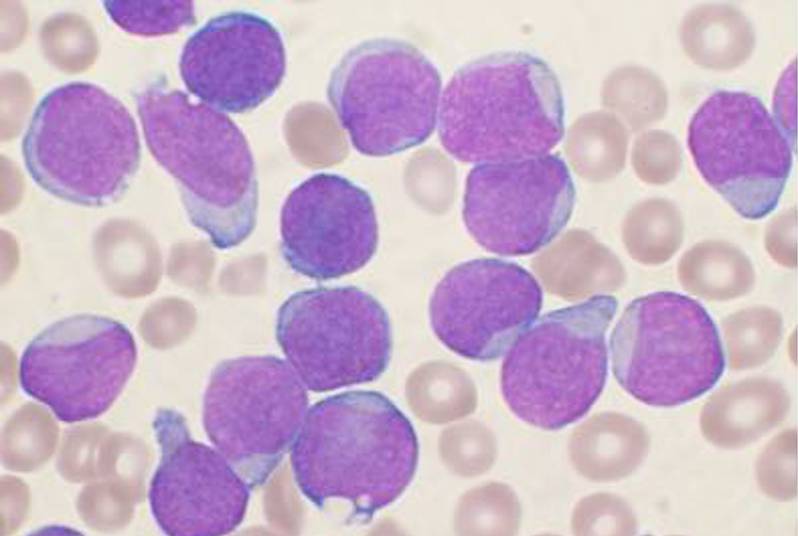

The news that your child has cancer always comes as a shock, but for one cancer, acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), parents can take comfort in the fact that doctors are really good at treating it. The cure rate for ALL has, over the last 40 years, climbed to nearly 90 percent.

Less comforting is the fact that some 10 to 20 percent of children who initially respond well to treatment suffer a relapse within five years. And right now, the drugs at our disposal aren’t very good at turning a relapse back into a remission.

“We have standard treatment regimens for newly diagnosed and relapsed ALL, both of which rely heavily on corticosteroids like prednisone and dexamethasone,” says Lewis Silverman, MD, director of the Pediatric Hematologic Malignancy Service at Dana-Farber/Children’s Hospital Cancer Center (DF/CHCC). “But we know that leukemias with any level of steroid resistance are more likely to relapse. Anything we can do to overcome that resistance would let us help many children.”

Silverman has launched a clinical trial that will try a new strategy for tearing down ALL cells’ barriers against corticosteroids.

Adding mTOR inhibitors

That strategy centers on a drug called everolimus, which blocks a protein called mTOR. The protein acts as kind of a cellular router: It directs signals from outside the cell to mechanisms that drive cell growth, protein production and metabolism. mTOR is the subject of intense research at DF/CHCC and Boston Children’s Hospital because it plays key roles in diseases ranging from cancer to neurocognitive disorders, premature aging disorders and kidney disease.

In the case of relapsed ALL, hematologist Scott Armstrong, MD, PhD, also of DF/CHCC, found in laboratory experiments that mTOR-blocking drugs could make cells from patients with relapsed ALL more vulnerable to steroid treatment. “We started by examining which genes get expressed in relapsed ALL cells that respond to prednisone compared with cells that resist it,” he says. “We found a gene pattern suggesting that an mTOR blocker could help make the resistant cells vulnerable.

“When we treated steroid-resistant ALL cells with rapamycin, an older mTOR blocker,” Armstrong continues, “the cells quickly became steroid-sensitive. The drug could even kill some off entirely on its own.”

Silverman and Armstrong ran a very small proof-of-concept clinical study in 2007, giving rapamycin with corticosteroids to children and adults with relapsed ALL for a few days before starting a standard chemotherapy regimen. “We wanted to know whether Scott’s lab results actually played out in people,” Silverman explains.

And indeed they did: “We saw the numbers of cancer cells in the patients’ blood drop dramatically while they took rapamycin and, in some cases, rise again when they stopped taking it, even though they continued on steroids and other drugs.”

In the new trial—which is currently recruiting patients—Silverman is testing whether adding everolimus to the standard regimen for relapsed ALL is feasible and safe. “Might there be too many side effects?” he asks. “We don’t yet know, but everolimus and similar drugs have been used on their own in children and adults for many years, and have good safety profiles.”

Silverman has high hopes for everolimus, should it earn its salt in this trial. “If it works as we think, then we would want to test it in children with newly diagnosed ALL. Everolimus might let us reduce the amount of steroids we have to give ALL patients, which could help children avoid some of the side effects of long-term steroid treatment like weight gain, bone and joint problems and increased infection risk,” he says.

It might also help reduce the risk of relapse in newly diagnosed patients. “It appears to work together with the drugs we already use and make them work even better. Adding it to our current treatment may make it possible to cure even more patients with ALL.”

Related Posts :

-

Exposing a tumor’s antigens to enhance immunotherapy

Successful immunotherapy for cancer involves activating a person’s own T cells to attack the tumor. But some tumors have ...

-

Combining CAR-T cells and inhibitor drugs for high-risk neuroblastoma

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy is a potent emerging weapon against cancer, altering patients’ T cells so they ...

-

Could a GI bug’s toxin curb hard-to-treat breast cancer?

Clostridium difficile can cause devastating inflammatory gastrointestinal infections, with much of the damage inflicted by a toxin the bug produces. ...

-

Making immunotherapy safe for AML

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML), the second most common leukemia in children, is hard to treat and has a five-year survival ...