How do you implement change? Lessons from a QI project in the NICU

Kristen Leeman, MD, is Director of Quality in the Division of Newborn Medicine and Associate Medical Director of the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Boston Children’s Hospital.

What if you were taught to do things a certain way, the way things were always done, and then a randomized clinical trial comes out supporting a different practice? How do you change effectively and efficiently and persuade your colleagues to do so? How do you ease fears around that practice change? How do you measure compliance and consistency?

As the Director of Quality in the Division of Newborn Medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital, I am charged with implementing practice changes in the NICU when scientific discoveries support them, improving the quality of care we deliver to our babies. Quality improvement (QI) science includes several key parts: multidisciplinary involvement in project prioritization, measurement planning, fostering buy-in, and leading small-scale tests of change before actual implementation. Once the change is implemented and improvement is sustained, we write up our work for publication to allow widespread impact.

But getting multidisciplinary teams to change established practice entails several challenges. A current project on platelet transfusions is a case in point.

Rethinking platelet transfusions

The platelet count threshold at which platelet transfusions are administered to newborns is highly variable. Neonatal thrombocytopenia is defined as a platelet count below 150,000/µL. Traditionally, we used a conservative threshold, giving transfusions at relatively high platelet counts, due to fear that lower counts would lead to increased bleeding risk in premature newborns. Some neonatologists would transfuse premature neonates as soon as the platelet count neared 50,000/µL.

A recent randomized trial, however, found a significantly greater rate of death or major bleeding when transfusions were given at higher versus lower platelet thresholds. The evidence supports not transfusing many newborns unless platelet counts drop below 25,000/µL.

Based on the new data, our Boston Children’s Hospital QI team developed thoughtful guidelines to reduce unnecessary and potentially harmful platelet transfusions. Using the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Model for Improvement as a framework, we performed “Plan-Do-Study-Act” cycles that included guideline development, staff education, and clinical pathway development. The QI team included key contributions from platelet experts Martha Sola-Visner, MD, who helped define the transfusion eligibility criteria and recommendations based on individual patient risks, and Patricia Davenport, MD, who led the data collection, educational efforts, and project management.

Getting the NICU’s buy-in

Addressing clinicians’ questions head-on helped improve buy-in and increase compliance with the recommendations. When clinicians expressed discomfort or fear with allowing platelet levels to drop lower than what they were used to, we listened and addressed their concerns with evidence. When appropriate, we adjusted the guideline to address their question.

For example, we adjusted our guideline to clearly define active bleeding, a scenario in which the guideline would not apply. We clarified that oozing from the umbilical line or pink-tinged secretions from breathing-tube secretions did not qualify as active bleeding, and therefore those babies would be covered by the new recommendations. We also created helpful tools, such as a guide in which clinicians can follow question prompts that easily point toward recommendations. Clarifications to the tool over time led to improved understanding and comfort with the practice change.

Tracking the effects of practice change

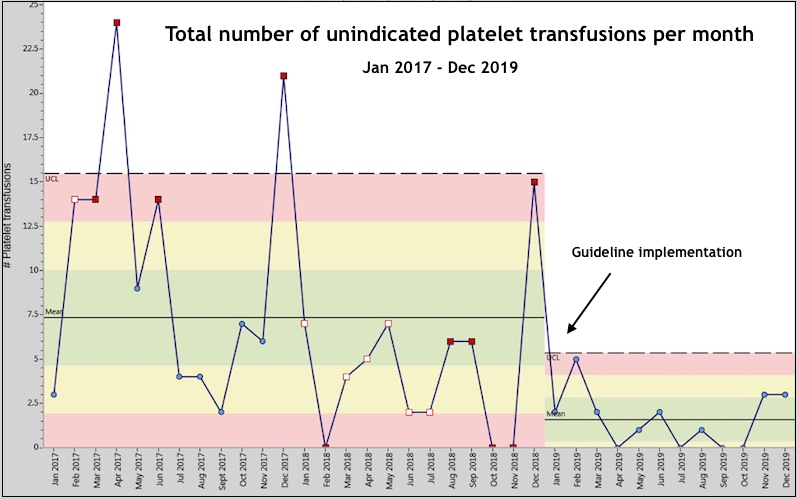

We conducted a three-year study that spanned two years before and one year after guideline implementation to measure adherence and outcomes. After implementation, our NICU’s mean number of non-indicated transfusions decreased from 7.3 to 1.4 per month in a QI chart analysis. The percentage of patients with non-indicated transfusions decreased from 4.5 percent to 1.1 percent after guideline implementation. When calculated per 100 patient admissions, the rate of non-indicated transfusions decreased from 12.51 to 2.59.

Notably, we saw no change in rates of intraventricular hemorrhage. Overall, we were able to rapidly translate cutting edge discovery to directly improve clinical care. We look forward to publishing these exciting project results in full.

Keys to success

Other recent examples of published quality improvement projects include a project to increase access to lactation services in the NICU, which improved rates of breast milk use, a guideline to decrease use of non-indicated acid-suppressing medication in newborns, and use of laboratory monitoring to increase rates of iron sufficiency in the NICU.

Implementation of widespread change can be a daunting task to address. But with leadership buy-in, a focused approach to education, and starting with small scale tests, successful change is possible. Key steps along the way include input from multidisciplinary staff, active listening to staff, and active use of feedback to make guideline adjustments as needed. Reporting progress back to staff throughout the project is also key, fostering a culture of change and celebration of successes.

Related Posts :

-

Mending injured hearts: Lessons from newborns?

When the heart is injured, as in a myocardial infarction, the damaged heart muscle cannot regenerate — instead, scar tissue forms. ...

-

Helping clinicians embrace family-centered rounds

If you’ve ever been hospitalized, you may have experienced this: groups of doctors coming in and talking about you ...

-

Infantile spasms: Speeding referrals for all infants

Infantile epileptic spasms syndrome (IESS), often called infantile spasms, is the most common form of epilepsy seen during infancy. Prompt ...

-

An off-the-shelf tamponade kit provides surgeons with ‘the luxury of time’ during a life-threatening emergency

It was a late Friday afternoon in April when the call came: A young boy was being transferred to Boston ...