Protecting against HIV by tricking the immune system

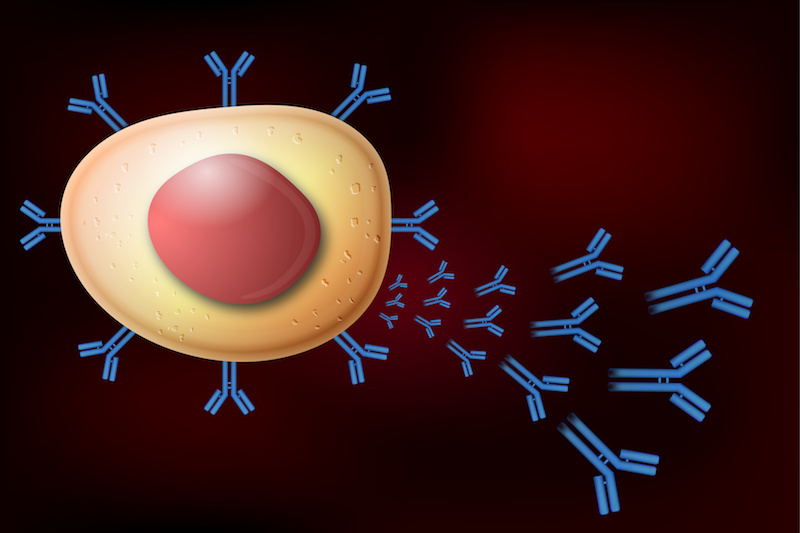

In making an HIV vaccine, a major goal is to stimulate production of broadly neutralizing antibodies that can fight multiple strains of the frequently changing virus. To date, experimental HIV vaccines haven’t been able to induce these kinds of antibodies. In fact, the immune system actively stops their production, seeing them as a threat.

Another challenge is that broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) require specific genetic changes that occur only rarely in the B cells that generate them. But researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital and the Duke Human Vaccine Institute (DHVI) have come up with an immunization approach that may allow bnAbs to survive and multiply to fight HIV. Their findings appear this week in Science.

Steering antibody development for a better HIV vaccine

When people are exposed to HIV (or any pathogen), they first make precursor antibodies. These then mature via mutation coupled with natural selection. Through more exposures and many iterations, the antibodies evolve to become more protective over time.

“Mice that express human broadly neutralizing antibodies have provided powerful new model systems in which we can iteratively test experimental HIV vaccines,” Alt explains.

Frederick Alt, PhD, and Ming Tian, PhD, of Boston Children’s storied Program in Cellular and Molecular Medicine previously developed mouse models that capture this process in a rapid way to ultimately generate bnAbs. With these models in hand, the researchers — including co-lead authors Kevin Saunders, PhD, Kevin Wiehe, PhD, and Priyamvada Acharya, PhD of the DHVI — traced the rare mutations needed for bnAbs.

They then engineered a series of HIV vaccine immunogens that preferentially bound to intermediate-stage bnAbs with these mutations. Through sequential vaccinations, they “persuaded” the immune systems of the mice to favor the rare mutations and allowed B cells with these mutations to develop and make neutralizing antibodies with a strong affinity for HIV envelope proteins. Immunization of non-human primates with this approach also elicited potent neutralizing antibodies.

Read more from DHVI.

Related Posts :

-

Building better antibodies, curbing autoimmunity: New insights on B cells

When we’re vaccinated or exposed to an infection, our B cells spring into action, churning out antibodies that are ...

-

Exposing a tumor’s antigens to enhance immunotherapy

Successful immunotherapy for cancer involves activating a person’s own T cells to attack the tumor. But some tumors have ...

-

Could we intervene in Huntington’s disease before symptoms appear?

Huntington’s disease is the most common single-gene neurodegenerative disorder and is characterized by motor and cognitive deficits and psychiatric ...

-

Could the right dietary fat help boost platelet counts?

Aside from transfusions, there currently is no way to boost people’s platelet counts, leaving them at risk for uncontrolled ...