In surgery for people with sepsis, choice of anesthetic may matter

Sepsis, an extreme immune response to infection, has no specific treatment and is a leading cause of hospital deaths. As part of their care, patients often undergo imaging procedures and surgery to pinpoint and help eliminate the infection. New preclinical findings suggest that the choice of general anesthetic used for these procedures can influence sepsis outcomes.

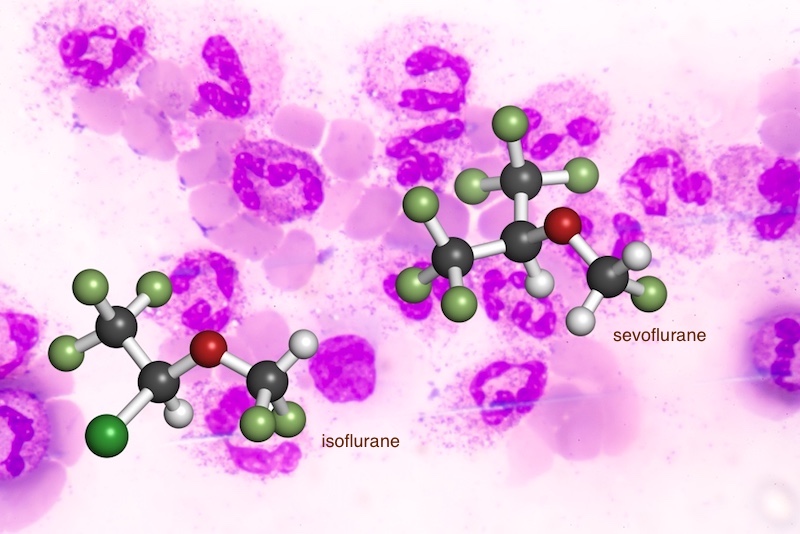

Quite separate from their anesthetic effects, the two inhaled anesthetics studied were found to alter the immune system — enough to improve or worsen sepsis in a mouse model, researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital report in The FASEB Journal.

“This study shows for the first time that sevoflurane improved sepsis outcome, but isoflurane worsened it,” says Koichi Yuki, MD, of the Division of Cardiac Anesthesia in Boston Children’s Hospital’s Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain Medicine.

Comparing sevoflurane and isoflurane

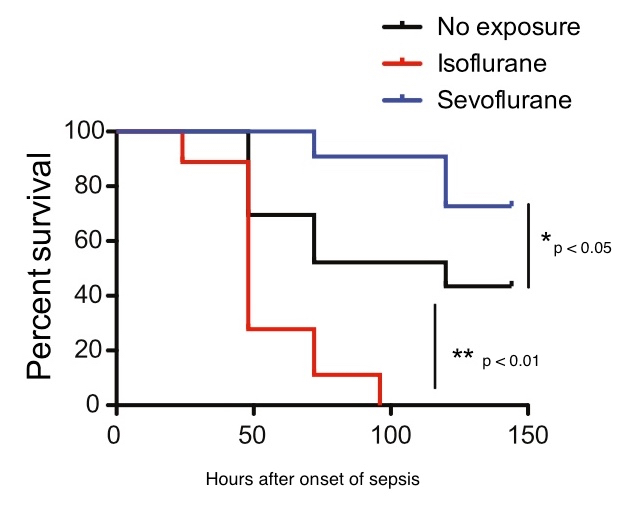

The study assigned 40 mice with abdominal sepsis to one of three groups. The first two groups received general anesthesia with either sevoflurane or isoflurane, the two most commonly used inhaled anesthetics. The remaining mice received neither of the two anesthetics and served as controls.

Septic mice receiving sevoflurane had significantly better survival than both the control and isoflurane groups. The isoflurane group did even worse than the controls — supporting the results of another recent study by Yuki’s team. Six days after the onset of sepsis, about 70 percent of the sevoflurane group was still alive, as were about half of controls. In contrast, the entire isoflurane group had died by the end of four days.

Immune effects of general anesthetics

Examination of the animals’ tissues found that those receiving anesthesia with sevoflurane had fewer bacteria. They also had significantly less loss of neutrophils in the spleen through the cell-death process known as apoptosis.

“Neutrophils are critical first-defense immune cells to fight against microbes,” explains Sophia Koutsogiannaki, PhD, of Boston Children’s, the study’s first author.

When neutrophils were exposed to sevoflurane in a dish, they also showed reduced apoptosis. Molecular studies showed that sevoflurane blocked the binding of two proteins in the Fas apoptosis pathway, known as Fas D and FADD.

Isoflurane did not have these effects. In the earlier study, it was associated with higher bacterial loads. Working through a separate molecular mechanism, it led to fewer neutrophils showing up to fight infections and less ingestion of bacteria by neutrophils.

“Our study suggests that the selection of certain anesthetic drugs could be critical in the management of septic patients because their immunomodulatory effects could be large enough to affect sepsis pathophysiology,” says Yuki, the paper’s senior author.

Future directions

Aside from being in mice, the authors note that the mice in their model did not have other medical complications, as human patients with sepsis often do. To date, no studies have looked at the anesthetics’ effects on sepsis outcomes in a human setting.

“Validation of our findings in patients is urgently required,” says Yuki. “Outside of the main findings, this study suggests that neutrophil apoptosis could be a therapeutic target for sepsis, and that sevoflurane could be used as a prototype to develop novel inhibitors for neutrophil apoptosis for the treatment of sepsis.”

One possibility would be sevoflurane-mimetic drugs that have no anesthetic effects, he says.

The paper’s coauthors at Boston Children’s were Lifei Hou, Nathan Blazon-Brown, and Sulpicio Soriano in the Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain Medicine. The work was supported by the Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CHMC) Anesthesia Foundation and the NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01GM118277). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Related Posts :

-

BRD7 research points to alternative insulin signaling pathway

Bromodomain-containing protein 7 (BRD7) was initially identified as a tumor suppressor, but further research has shown it has a broader role ...

-

The people and advancements behind 75 years of Boston Children’s Cardiology

Boston Children’s Department of Cardiology has more than 100 pediatric and adult cardiologists, over 40 clinical fellows learning the ...

-

One day closer: Second opinion for urologic pain changes Iker’s life at last

Like many kids, Iker Guzman enjoys playing with LEGO toys. But there was nothing lighthearted about the day a few ...

-

Rowan the Remarkable: Defying the odds with CPAM

This is the story of a baby named Rowan and his remarkable journey of beating the odds after doctors discovered ...